Cercopes

Monkey-Like Trickster Spirits!

In between his Twelve Labors and having sex with women around the world, the Greek hero Heracles (or Hercules to the Romans) didn't really have time for personal hygiene.

But that doesn't mean he took kindly to people making fun of his stinky self. What happened when two criminals did just that? Heracles either laughed it off or bumped them off - or both!

Background on the Bad Boy and His Butt

After completing his Labors, Heracles went out seeking a spouse, since he'd already killed his first wife, Megara, and their kids.

His eye fell on Iole, daughter of King Eurytus of Oechalia, who'd promised his little girl to the man "who should vanquish himself and his sons in archery," says Pseudo-Apollodorus in the Library.

But even though Heracles won the archery contest (of course), Eurytus reneged on the bargain, since he was afraid his prospective son-in-law would murder his new wife like he did his first.

Arguing Heracles's case throughout all this was his Eurytus's son, Iphitus.

When a bunch of cattle went missing, Eurytus suspected Heracles, but Iphitus insisted his pal was innocent.

Frustrated with the entire situation, Heracles invited Iphitus to his home at Tiryns, but then got angry and threw his young friend off the city walls to his death. Unable to be purified for this crime, Heracles sought the advice of the Delphic Oracle, asking how he could atone for his misdeed.

The answer? He was sold into slavery - the money he brought at the auction block served as monetary compensation for Iphitus's death - and served Omphale, queen of Lydia, for three years. After a while, he started feeling better and decided to clear Lydia of local criminals.

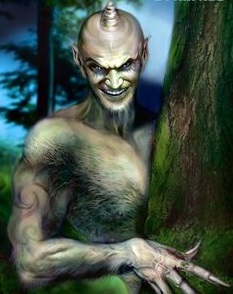

One such dastardly pair was the Cercopes, who Diodorus Siculus says were “robbing and committing many evil acts.” Heracles captured them at Ephesus. Surviving fragments of a hymn to the Cercopes describe them as “two brothers living upon the earth who practised every kind of knavery,” and they’d earned their nickname of “Cercopes,” or “monkey-men,” due to their mischief.

Their names vary depending on the version of the myth being told – we’ll call them Passalus and Acmon, as in that hymn, for expediency’s sake – but one thing that was for sure was their mother’s warning to them.

Mama Cercopes told them to watch out for “Blackbottom,” or Heracles, who was the Rudy Giuliani of cleaning up Lydian crime at the time. Why did Heracles earn that moniker? Because of his hairy rear, of course!

Of course, Heracles didn’t leave these criminals untouched. He captured them, earning a rock near the Cercopes' hangout named after himself (although, as Herodotus says, it was just called Blackbuttock).

But Zeus, Heracles’s father, wasn’t content with his son’s heroic deeds in getting the bad guys. Passalus and Acmon were either turned into stone, or, as Ovid claims in his Metamorphoses, they were turned into “ disgraceful creatures” to match their bad behavior.

Zeus covered their bodies with yellow fur and turned them into monkeys, but didn’t stop there. “He contracted their limbs, turned up and blunted their noses, and furrowed their faces with the wrinkles of old age,” then “robbed them of the power of speech, and those tongues born for dreadful deceit, leaving them only the power to complain in raucous shrieks.”

As his final punishment, Zeus sent the monkeys to an island in Italy that Aeneas eventually passed; it received the name of Pithecusa, “named after its inhabitants, from pithecium, a little ape.”

Monkey Business or Comedy?

But every ancient myth about these bad boy brothers focused on their crimes and punishments. In fact, there’s a long tradition of laughter associated with the Cercopes.

One of the best-known versions of the Cercopes tales was frequently articulated in ancient art, but we have no surviving literary evidence of it until the works of pseudo-Nonnus in the fifth century A.D.

That writer recounts how the Cercopes’ mother told them again to avoid a guy with a dark butt, but to no avail.

In this version, though, the brothers come across Heracles asleep under a tree, his weapons resting on the trunk. They tried to steal his arms, but “Heracles at once noticed, seized them and carried them off, tied head-downwards to a piece of wood.”

Only when they were hanging upside down (like monkeys, interestingly) did they notice Heracles’s rear end was “black with the thickness of hair”—he was the man of whom their mother had warned them! The brothers gossiped about it, which “made Heracles roar with laughter,” and he let them go.

This version is a far cry from monkey-fication or being turned to stone!

As classicist Ralph Rosen notes in Making Mockery: The Poetics of Ancient Satire, this tale is a “remarkable comic version of the typical revenge-through-punishment motif” that recurs across Heracles’s travels. Usually, the hero avenges himself by harming someone, whether the individual was guilty or innocent (like Megara and Iphitus).

Here, Heracles has a sense of humor about himself and lets the Cercopes off practically unscathed with no violent acts—very uncharacteristic! Rosen proposes that this version of the story is an insight into how the ancient Greeks may have regarded comedy and humor in their mythic structure.

In fact, cursing and verbal abuse, as the Cercopes brought down on Heracles by gossiping about his butt, was quite a common feature of Greek comedy.

Rosen posits that this myth shows the “transformative” and “therapeutic powers of laughter.” The myth is somewhat voyeuristic in this interpretation.

Basically, the Cercopes respond as if they were watching a funny play, eacting to “something they think is humorous … and as such respond as members of an audience moved to laughter by a comic spectacle.”

And Heracles participates in this comic action by inverting the normal physical position of the Cercopes by slinging them upside down and over his shoulders, which is “intrinsically comic for Greek culture.” Looks like even big Herc has a sense of humor, after all!

[1]