Scylla

The monstrous sea goddess

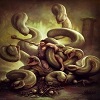

Scylla was a monster that lived on one side of a narrow channel of water, opposite its counterpart Charybdis.

The two sides of the strait were within an arrow’s range of each other—so close that sailors attempting to avoid Charybdis would pass too close to Scylla with disastrous results.

Various Greek myths account for Scylla's origins and fate. According to some, she was one of the children of Phorcys and Ceto. Other sources, including Stesichorus, cite her parents as Triton and Lamia. According to John Tzetzes and Servius' commentary on the Aeneid, Scylla was a beautiful naiad who was claimed by Poseidon, but the jealous Amphitrite turned her into a monster by poisoning the water of the spring where Scylla would bathe.

A similar story is found in Hyginus, according to whom Scylla was the daughter of the river god Crataeis and was loved by Glaucus, but Glaucus himself was also loved by the sorceress Circe. While Scylla was bathing in the sea, the jealous Circe poured a potion into the sea water which caused Scylla to transform into a monster with four eyes and six long necks equipped with grisly heads, each of which contained three rows of sharp teeth. Her body consisted of 12 tentacle-like legs and a cat's tail, while four to six dog-heads ringed her waist. In this form, she attacked the ships of passing sailors, seizing one of the crew with each of her heads.

In a late Greek myth, recorded in Eustathius' commentary on Homer and John Tzetzes, Heracles encountered Scylla during a journey to Sicily and slew her. Her father, the sea-god Phorcys, then applied flaming torches to her body and restored her to life.

Between Scylla and Charybdis (The myth and the proverb):

Scylla and Charybdis were mythical sea monsters noted by Homer; Greek mythology sited them on opposite sides of the Strait of Messina between Sicily and the Italian mainland. Scylla was rationalized as a rock shoal (described as a six-headed sea monster) on the Italian side of the strait and Charybdis was a whirlpool off the coast of Sicily. They were regarded as a sea hazard located close enough to each other that they posed an inescapable threat to passing sailors; avoiding Charybdis meant passing too close to Scylla and vice versa. According to Homer, Odysseus was forced to choose which monster to confront while passing through the strait; he opted to pass by Scylla and lose only a few sailors, rather than risk the loss of his entire ship in the whirlpool.

Because of such stories, having to navigate between the two hazards eventually entered idiomatic use. Another equivalent English seafaring phrase is, "Between a rock and a hard place". The Latin line incidit in scyllam cupiens vitare charybdim (he runs on Scylla, wishing to avoid Charybdis) had earlier become proverbial, with a meaning much the same as jumping from the frying pan into the fire. Erasmus recorded it as an ancient proverb in his Adagia, although the earliest known instance is in the Alexandreis, a 12th-century Latin epic poem by Walter of Châtillon.

SCYLLA (princess)

In Greek mythology, Scylla (Ancient Greek: Σκύλλα) is a princess of Megara.

Mythology

As the story goes, Scylla was the daughter of Nisus (Nisos) the King of Megara, who possessed a single lock of purple hair which granted him and the city invincibility. When Minos, the King of Crete, invaded Nisus's kingdom, Scylla saw him from the city's battlements and fell in love with him.

In order to win Minos's heart, she decided that she would grant him victory in battle by removing the lock from her father's head and presented it to Minos. Disgusted with her lack of filial devotion, he left Megara immediately. Scylla did not give up easily and started swimming after Minos's boat. She nearly reached him but a sea eagle, into which her father had been metamorphosed after death, drowned her.

Scylla was transformed into a seabird (ciris), relentlessly pursued by her father, who was transformed into a sea eagle (haliaeetus).

Scylla's story is a close parallel to that of Comaetho, daughter of Pterelaus. Similar stories were told of Pisidice (princess of Methymna) and of Leucophrye. The story of al-Nadirah told by al-Tabari and early Islamic writers are considered by Theodor Nöldeke to be derived from the tale of Scylla.

Scylla appears in Alexander Pope's mock-heroic "Rape of the Lock" as part of an extended representation of gallant chatter round a card table in the guise of a heroic battle:

Ah cease, rash youth! desist ere 'tis too late,

Fear the just gods, and think of Scylla's fate!

Chang'd to a bird, and sent to flit in air,

She dearly pays for Nisus' injur'd hair!

"Rape of the Lock", canto III.

Sources

Ovid, Metamorphoses VIII, 6-151, esp. 154-151

Hyginus, Fabulae, 198

Virgil (2007). Aeneid.

Homer, Odyssey 12.124–125

Ovid, Metamorphoses 13.749

Apollodorus, E7.20

Servius on Virgil Aeneid 3.420

schol. on Plato, Republic 9.588c.

Hesiod fr. 200 Most [= fr. 262 MW] (Most, pp. 310, 311).

Acusilaus. fr. 42 Fowler (Fowler, p. 32).

Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica 4. 828–829 (pp. 350–351).

Stesichorus, F220 PMG (Campbell, pp. 132–133).

Hyginus, Fabulae Preface, 151.

John Tzetzes, On Lycophron 45

Servius on Aeneid III. 420.

Hyginus, Fabulae, 199

On Lycophron 45

Ovid, Metamorphoses xiii. 732ff., 905; xiv. 40ff.

Ovid, Metamorphoses xiv.51–2

Endymion Book III, line 401ff – via Project Gutenberg

"Greek Legends and Myths"