Battle of Plataea

The Battle of Plataea - August, 479 BCE

The invasion that began as a punitive attack by Persia against a collection of disunited cities ended in one of the most critical battles ever fought on European soil. North of Athens, on the far side of a mountain range that separated Attica from Boeotia, the contest would be decided. Here the Greek style of decisive, heavy infantry combat, which for the most part had only been seen during the internecine wars amongst the Greeks, would be put to the test in the fields outside of the town of Plataea by the richest and most powerful empire in the world.

At Marathon, in 490 BCE, massed formations of armored Greek infantry defeated a Persian army designed for warfare on the open plains of Asia. Ten years later, at the pass of Thermopylae, the Persians under King Xerxes triumphed, but it was a victory achieved by sheer weight of numbers. Even without the treachery of Ephialtes - the Greek who showed Xerxes' Immortals a "backdoor" route around the Greek position, the 7,000 Greeks, led by 300 Spartans, would eventually have succumbed to the invasion force of over a quarter million. A month later, the naval engagement in the straits of Salamis halted the Persian advance westward, but left Athens and the larger portion of Greece in enemy hands. During the following autumn, winter and spring. the Persian invasion force ebbed and flowed with the seasons, in search of provender, eventually settling around the city of Thebes. Out of sheer necessity Thebes and the other cities of central and northern Greece had come to terms with Xerxes, supporting his army with both supplies and men. In fact Thebes and Athens had been at odds before, so it took little prodding by the Persians to obtain the commitment of Theban arms in the conflict.

Greek Forces

The Greek army, according to Herodotus, totaled around 30,000 hoplites with double that number of light troops. 5,000 Spartiates took part in the battle, while the Athenians provided 8,000 heavy infantry. The remaining units were comprising mostly from other city-states of the Peloponnese. The Greek numbers he details, unlike the Persian counts, appear to be likely. This entire force was under the command of the Spartan regent Pausanias.

The Spartans or Spartiates, arguably the finest infantryman of any era, formed the core of the Greek forces. Their martial training began at age seven, when they were taken from their homes and placed in "herds", barracked as soldiers and toughened both physically and mentally. This military schooling was dubbed the Agoge or Upbringing. At the end of adolescence, and as a requirement of "graduation", each prospective Spartiate was sent off for almost an entire year to endure the wilds of Lakonia, to live alone and apart from society, utilizing all the skills acquired in the Agoge to survive. To complete the initiation to full Spartan citizenship, each young man must then be admitted to a phidition or dining-mess of fifteen warriors. Here and amongst his mess-mates he would spend most of his time when not engaged in war or training. The Spartans, through their dominance of the Peloponnesian peninsula, proved instrumental in ensuring the participation of the remaining free Greeks.

The Athenian warriors, and for that matter the other Greek allies, were part-time militia, their training beginning late by Spartan standards; they enrolled as epheboi at eighteen, and by the time they reached their twentieth birthday compulsory military training was complete.

By the Archaic period infantry combat in the Greek world had evolved from the individual duels of aristocrats and tribal leaders described by Homer, to the densely packed hoplite formation. Typically files of eight men deep, with shields overlapping shields, advanced under the weight of seventy pounds of armor and weapons. Young, strong warriors were positioned in the front ranks, the less sure in the middle, while the rear rankers were made up of grizzled old veterans who ensured that no desertions took place once the battle commenced. The ones behind would often push the men in front with the bowls of their shields, while the front-rankers thrust and hacked with eight-foot spears or their back up weapon, the two foot long hoplite sword.

This mode of fighting proved effective as long as every man stood his ground, covering both him and the man to his left with his large, round shield. The shield itself was large and heavy, often a meter in diameter and approaching twenty pounds in weight; it was fashioned from oak planks fitted and shaped like a large bowl with a rim of several inches and held by the hoplite by a central arm band through which he slid his forearm, and gripped by a handle just inside the rim. The entire wooden core could be either bare, covered with leather, or faced with a thin sheet of bronze. The remainder of the panoply, or outfit, consisted of either a bronze breastplate of thirty pounds or a laminated linen or leather corselet, bronze helmet, and bronze greaves. This panoply would vary in completeness based on the relative affluence of the hoplite. It is not hard to imagine what a burden this would have placed on a 140 pound man in the heat of a Greek summer!

Persian Forces

Herodotus places the total number of forces under the command of the Persian general Mardonios at 300,000. This, like all his tallies of enemy contingents, seems inflated. Peter Green in his book, The Greco-Persian Wars, speculates the Persian force to be roughly equivalent to the Greeks. Peter Connolly, author of Greece and Rome at War, conjectures, based on the reported size of Mardonios' stockade, that the force could have been as large as 120,000.

The Persian army, and the conscripts of the subject nations, were built for speed and maneuverability. The bow, short lance, and dagger-like sword (akinakes) filled out the weapons available to the Persian infantryman. The elite units, such as the Immortals, may have had scaled armor corselets, but their shields would have been constructed of leather covered wicker-work, and helmets, if worn at all, would have resembled elegant bronze funnels that sat atop their heads.

Deployment

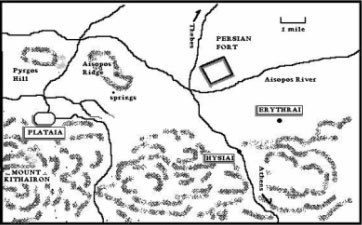

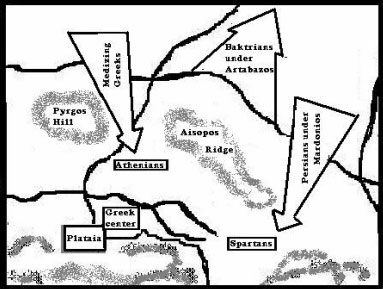

The allied Greek forces assembled at the sanctuary of Eleusis before moving north and over the mountains, taking the main Thebes Road through the Eleutherai Pass, by-passing the closer Dryocephalai Road, which descends from Mount Kithairon near the town of Plataea. As they descended to the foothills lead elements, most likely light troops (euzonoi), would have seen an immense stockade erected by the Persians on the far bank of the Aisopos River, looming near a bridge. The invaders' frontlines would have stretched for several miles, mimicking the course of the river. Since no attempt was made by the Persians to hold the mountain passes, we can conjecture that Pausanias sent light troops ahead, maybe by days, to secure these passes. Pausanias brought his forces to the lower slopes of the mountain range near the village of Hysiai, his Spartans moving east of the road to Erythrai, the Athenians west toward Plataea and the Peloponnesians and other troops taking up the center. Positioned on the open and level ground near the road the Megarians would be the first to see action.

Day One

Mardonios, from his frontlines on the Aisopos, sighted the Greeks and particularly the Megarians in their vulnerable spot along the road. Immediately, he ordered his elite cavalry, captained by the Persian Masistios, to attack. The swarming horsemen launched a punishing missile assault that pushed the Megarians to the edge of withdrawal. Their pleas for help were answered by a contingent of Athenian bowmen. In the action that followed Masistios was killed and the Persians withdrew to their side of the Aisopos. Both sides licked their wounds. The Greeks held fast to this line, awaiting another Persian attack, but when this failed to materialize Pausanias moved along the lower slopes, just off the plain, toward the west and Plataea.

Day Two - Day Seven

As the Greeks redeployed to the west, Herodotus relates a dispute between the Tegeans and the Athenians for the second place of honor on the left flank. After a debate the Athenians won out, retelling of their victory at Marathon and their leading naval role at Salamis. They took up position atop Pyrgos Hill, the Spartans on the right of the Aisopos Ridge, while the remaining Greek allies filled the center. Mardonios, whose line overlapped the Greeks at both flanks shifted westward also, his Persians on the north side of the river facing the Spartans, Artabazos with his Baktrians and Medes facing the Greek center, and on the far flank across the river from the Athenians, the Medizing Greeks fashioned their lines. During the next several days sacrifices were made to the gods, the omens interpreted, and the answer for both armies cautioned about advancing across the Aisopos River. All the while the ranks of the Allied Greeks swelled as more troops wended their way over Kithairon.

Day Eight

Frustrated by the Greeks reluctance to engage, Mardonios ordered a cavalry detachment to swing around behind the Greeks and attack their supply lines. Wagons and carts would have to cross the flat plain between the foothills and the Aisopos ridge. By nightfall hundreds of provender wagons had been either burned or captured.

Day Nine - Day Eleven

Deprived of supplies, Pausanias still clung to the ridge and his superior defensive position. Each day Mardonios unleashed his cavalry units, which rode to within missile range of the Greek frontline, launching barrage upon barrage into the static files of hoplites. Each day the Greeks endured these attacks and stood fast upon the high ground.

Day Twelve

With the passing of every day Mardonios knew the Greeks facing him across the river grew in numbers. Although his cavalry raids did indeed cut the enemy's supply lines, reinforcements continued to trickle to Pausanias by way of the Dryocephalai Road. At this time Herodotus inserted two incidents into his narrative, apparently for dramatic effect. Firstly Mardonios dispatched a herald to personally issue a challenge to Pausanias - send out a number of Spartans and he, Mardonios would march out with an equal number of Persians. The victors would determine the fate of both armies. The second is even less probable and must be attributed to the hazy memory of one of the Athenian veterans he interviewed many years after the battle.

Suddenly Pausanias decided to switch positions with the Athenians - to place them against the Persians, which they had beaten ten years earlier at Marathon, leaving the Spartans to face the Medizing Greeks, enemies with which they would have been very familiar. It seems very unlikely that any sensible general would attempt such a move in the face of daily cavalry attacks, and it is on the whole unlikely in an age when the position of honor (the right flank) would have, by reputation and expectation, fallen to the Spartans.

Again Mardonios ordered his raids, but this time with the purpose of spoiling the Greeks' main water supply at the Springs of Gargaphia. By some method, the details of which have not come down to us through Herodotus, the Persians succeeded in destroying the spring. This final raid, or the prospect of losing more wagons in the plain between Plataea and his position on the ridge, compelled Pausanias to act. That night, under cover of darkness, he would move the army back toward Plataea, obtain water and secure his supply lines once again.

Day Thirteen - Final Attack

Again Herodotus spices up the story: Pausanias calls a meeting of commanders to dispense orders for the withdrawal, but one of his own Spartan polemarchs, Amompharetos, refuses to retreat in the face of the enemy. He raises a large boulder, like a voting pebble, and casts his ballot to hold the ridge. Again, an unlikely story-Athenians, not Spartans voted using pebbles; Spartans cast their ballots by shouting! This argument is the supposed reason for the delay of the Spartan, Lakonian and Tegean contingents from leaving the ridge until daylight. Pausanias orders the retreat of the remainder of his Spartans and the other allies, hoping that his departure will compel Amompharetos to withdraw. More likely, as Ernle Bradford surmised in his book, Thermopylae:the Battle for the West, this entire event was a carefully planned rearguard action, the bait needed to lure Mardonios across the Aisopos River.

As day broke, Persian pickets sounded the alarm at the sight of the empty ridges to the south. Mardonios, encouraged by the news, and thinking he could catch the Greeks in a panicked retreat, ordered a full attack. By the time the Persians crossed the Aisopos and rolled over and around the ridge line, the Spartans, Greek center, and Athenian contingents became dangerously separated into three distinct formations, unable to offer assistance to each other.

The Spartans formed up quickly onto a piece of ground with a slight rise, offering them limited protection from cavalry, and having walked the battlefield recently, I can attest to the fact that even the level ground (outside of the tilled fields) is hardly level, for it is pocked and potholed, and strewn with boulders and clumps of grass. In low light conditions it would most likely be a dangerous place for horses to traverse. Here the Spartans, Lakonians, and Tegeans locked their shields and waited as Persian bowmen planted their shields at bow range and launched a torrent of arrows. Meanwhile the Corinthians and other Peloponnesians who comprised the Greek center fell back to the town of Plataea. In the plain between the town and Pyrgos Hill, the Athenians were overtaken by the Theban army. The fighting continued throughout the morning, the Spartans hunkering down, the Athenians in a hoplite battle, and the Greek center disconnected and waiting while more and more Persians streamed from their positions on the river toward the Spartans, Lakonians and Tegeans. Finally the Tegeans moved, inducing the Spartans to attack also. This long delay of the Spartans Herodotus attributes to unfavorable omens as Pausanias performed sacrifice after sacrifice. While it was true that no Spartan commander would initiate an attack without the gods' consent, Mardonios had struck first, relieving Pausanias of any such concern. It is more likely that he stalled his attack until the weight of the Persian reinforcements pressing forward provided a dense and immobile target.

According to Herodotus, "First there was a struggle at the barricade of shields; then the barricade down, there was a bitter and protracted fight, hand to hand... for the Persians would grab hold of the Spartan spears and break them; in courage and strength they were as good as their adversaries, but they were deficient in armor, untrained and greatly inferior in skill. Sometimes singly, sometimes in groups of ten-perhaps fewer, perhaps more, they fell upon the Spartan line and were cut down."

But still the contest was in doubt. The Persian mounted troops, under personal command of Mardonios, began to push the Spartans back, and the battle might have been won by the Persians but for the strong arm of a Spartan soldier. With the toss of a stone, Mardonios was unhorsed. Without their leader the Persian formation began to lose its cohesiveness; the Spartans heaved forward. The troops who made up the Greek center advanced on the run at the sight of the Persians reeling under the Spartan surge. Artabazos, seeing this also, retreated hastily with 40,000 troops, men who never had to unsheathe their swords!

The Greeks moved north relentlessly, crossed the river and closed on the Persian stockade. The Tegeans were the first to breach the fort and enter. By the time the battle ended less than 3,000 of Mardonios' troops survived. Herodotus counts the Greek dead as follows: 91 Spartans; 16 Tegeans; 52 Athenians; 600 Megarians, Corinthians and Phliasians combined.

Aftermath

As with all Greek battles, the loot was collected, trophies erected and funeral rites performed for the dead. Unluckly Thebes, the city that had thrown in with the Persians, held out for several weeks before finally surrendering. At the same time as this battle, the allied Greek fleet had defeated a Persian naval contingent that had landed at Mykale. These victories secured the Greek mainland from Persian invasion, but the war against Xerxes and his empire would go on for years.

Plataea today. The ruins in the foreground are of the ancient town. In the distance to the left is Pyrgos Hill, the position the Athenians held on the flank. The Spartan position would be just out of the frame to the right, following the low ridge. The flat plain just beyond the town is where the Boeotians and other Medizing Greeks engaged the Athenians on the last morning.

Bibliography

Diodorus Siculus Book XI , translated by C.H. Oldfather Harvard University Press 1989

Herodotus - The Histories , translated by Aubrey De Selincourt Penguin Classics 1972

The Greco-Persian Wars , by Peter Green University of California Press 1996

Greece and Rome at War , by Peter Connolly Prentice-Hall 1981

Pausanias-Descriptions of Greece , translated by W.H.S. Jones Harvard University Press 1964

Persia and the Greeks , by A.R. Burn Minerva Press 1962

Plutarch's Lives-Aristides , Dryden translation revised by Arthur Hugh Clough Random House 1992

Sparta , by H. Michell Cambridge University Press 1964

The Spartan Army , by Nicholas Sekunda Osprey Publishing 1998

Thermopylae:The Battle for the West , by Ernle Bradford Da Capo Press 1993

Studies in Ancient Greek Topography - Part III, by W.K. Pritchett University of California Press 1980

Warfare in Antiquity , by Hans Delbruk University of Nebrask Press 1990

Warfare in Ancient Greece , by Pierre Ducrey-translated by Janet Lloyd Schocken Books 1986

Warfare in the Classical World , by John Warry University of Oklahoma Press 1980

The Western Way of War , by Victor Davis Hanson Alfred A. Knopf 1989

Article by: Jon Edward Martin