The Napoleon Wars and the 100 Days Wars

The French were very displeased with the political leadership of King Louis XVIII. Although the King meant well, he proved to be incompetent.

The situation in France

The French were very displeased with the political leadership of King Louis XVIII. Although the King meant well, he proved to be incompetent.

In the King's wake the "émigrés" had returned to France: nobles and members of the clergy that had fled the country during the French revolution. Now they where back and they claimed, with a loud voice, their former privileges and the lands the owned before the revolution. The peasants who bought these lands for very low prices where of course very suspicious of a possible division of the lands amongst these "émigrés". France was mainly an agrarian nation in those day's and the mistrust of the largest part of the population undermined the King's position.

The mediocre attempts of the Bourbons to revive the unstable economy had no effects. The situation was far from good; the prices of food were sky-high because of a hard winter and a dry and very hot summer. The middle-class, that did so well under Napoleon's rule, was complaining about the bad economic situation and the poor and the needy had to live trough some very rough times.

Another large group of malcontents was the ex-soldiers. After their demobilisation in 1814, many of these men were able to continue their normal civilian lives. For a sizeable group of veterans, officers on half pay and ex-professional soldiers there was no place in the with inflation stricken society. Once they were conquering hero's bringing glory to France, now many of them were starving to death, deserted by that same France. It's only logical that they where unhappy and agitated.

On the international scene, everything looked favourable also. At the Vienna congress the understanding between the Powers was far from good and none of them really liked the French Bourbon government.

Napoleon's march on Paris

On March 1, 1815, Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte set once again foot on French soil at Golfe-Juan, between Cannes and Antibes. A more appropriate place to land would have been the valley of the Rhone river. From there the march to Paris would have been far easier and a lot faster. Bonaparte feared the royalist sentiments of the inhabitants of that region so he took the more difficult road through the Alps to Grenoble.

His arrival took the French authorities by total surprise. It took four day's for the news to reach Paris. The irresolution of the local authorities gave Napoleon the time to act without interference. The population, on whose reaction everything depended, reacted calm and resigned.

On March 7, 1815 the small Imperial column met the 5th Regiment of the Line, not far from Grenoble. Napoleon stepped forward and faced the muskets alone. With a remarkable mixture of exaggerations and lies and by using his charisma and personal power over soldiers, he managed to persuade the Regiment. With the cry: "Vive L'Empéreur" the 5th changed sides as one man. The gates of Grenoble opened and the Emperor received a warm welcome.

On March 8, the 7th Regiment of the Line and its commander, Napoleon's future Aide de Camps: Colonel Charles Huchet, Count de la Bédoyère changed sides too.

On every stop on his march to Paris Napoleon addressed the people. He promised everybody exactly what they wanted to have being the opportunist that he was. Peasants he assured that they would not lose their lands to the émigrés, city people he seduced with promises of fiscal reforms. Everywhere he went he promised peace and prosperity.

In the mean time the Bourbons issued a warrant for his arrest. They send increasing numbers of troops to intercept him. Marshal Ney promised Louis XVIII he would bring Napoleon to Paris "in an iron cage". When he met his former master eye to eye on March 18, 1815 the attraction proved to be too great and he defected also together with the 6.000 men in his command.

In Paris, a practical joker had put up a message on the Place Vendôme. It read: "From Napoleon to Louis XVIII: my dear brother, it is not necessary to send me more troops, I already have enough of them!".

Meanwhile, the mob became very restless. Revolutionary song's and slogans began to reappear. On March 19, 1815 Louis XVIII took the safe way out. Pressured by Napoleon's unstoppable march to Paris and the growing anti-royalist mood in Paris he ran in the middle of the night to Gent, Belgium (then still the Netherlands). Here he started a voluntary exile that would last for more than a hundred day's.

The Emperor back in power

Napoleon made his great entrance at the Tuilleries palace in Paris on March 20, 1815. Was his return this easy? No of course not:

Napoleon knew that war was inevitable but he did not proclaim a general mobilisation as off yet. It would only be a matter of time before his former enemies would turn on him but he desperately needed to get the French public opinion behind him so he pleaded for peace. He had hoped that at least some of the Powers would accept the fact that he was once again in charge in France, but that did not happen.

The representatives of the Powers met in Vienna on March 13, seven day's before the Emperor reached Paris. They declared him an outlaw and an enemy of world peace. They pledged to assemble armies to take care of him for once and for all.

On March 25, the Seventh Coalition was formed with the signing of a formal defence treaty between Britain, Austria, Prussia and Russia. While Britain and Prussia had already troops in the field, the other nations prepared themselves. All Powers broke of their official relations with Napoleon's France.

In France Napoleon's position was a very weak one. He had to make lots of compliance's to maintain himself. He nominated several members of the old nobility and even people that betrayed him in 1814 in high positions to get their much needed support. Off the about 730 députées in the chamber of representatives, only about 100 were on his side. The others watched his every move with eagle's eyes. This of course limited his freedom of actions a lot. In large parts of France, rebellion ruled. In the department of the Vendée an armed uprising broke out.

Preparations for war

Now that he could put the blame for the coming war on his enemies, Napoleon dropped his "angel of peace" act. He ordered a general mobilisation on April 8 but hesitated to reinstall the conscription. Louis XVIII had abolished this hated system when he came in power after Napoleon's first abdication.

There where big shortages on every possible kind of military equipment but with a lot of ordinance's and tremendous efforts most of them were, to some extend, resolved. The biggest problem however was the shortage of soldiers. The Royal Army that Napoleon inherited after Louis XVIII fled for Gent was about 200.000 troops strong. Some 75.000 former soldiers and some 15.000 new volunteers responded to their Emperor's call to arms. Police, Customs and Navy units changed into infantry and artillery regiments. Veterans and the battalions of the National Guard "Gardes Nationaux" entered active service. With these units an auxiliary army of some 220.000 men was formed, an army that provided the garrisons for the "places fortes" (fortresses) and the camps.

These and other measures supplied Napoleon with a force of some 290.000 troops. He had a prospect of some 150.000 more troops within 6 months, the militia class of 1815. These conscripts, put on extended leave when the conscription was abolished, would be recalled into active service.

The Allied plan of attack

Despite his efforts Napoleon's position was still far from favourable. In time the Allies could send between 800.000 and 1.200.000 soldiers in the field against him. They could freely choose their directions of attack along France's long borders.

The Allied commanders were very aware of this last advantage. Starting from April 1, their troops would march on Paris from different directions and in great strength. They hoped to crush the smaller French armies with their superior numbers.

Wellington and Blucher with about 110.000 Anglo-Dutch troops and some 117.000 Prussians would attack France from the Netherlands (Belgium since 1830). General Kleist von Nollensdorf would join Blucher with his 20.000 Prussians, stationed in Luxembourg.

Schwarzenberg and about 210.000 Austrians would attack from the Black Forest.

An army of 50.000 Austrians and 25.000 Piedmonts under the command of General Frimont threatened Lyons and the Rivièra and in Switzerland Bachmann and 37.000 Swiss were standing by.

A Spanish-Portuguese army was still forming but would attack as soon as possible in the south and a Neapolitan army under Onasca would invade Southeast France.

Barclay de Tolly's 150.000 Russians, which had the longest distance to travel, would stay in reserve in the central Rhine area after their arrival.

This was a pretty impressive set-up on paper but the implementation of it on the field did not go as planned. Late May 1815 only the armies of Wellington and Blücher were in place. The Austrians could not reach the Rhine before early July and the Russians would reach their positions much later than planned.

Napoleon's reaction

Napoleon could adopt two strategies to counter the Allied attack. His first option was to take a defensive posture. Assuming that the Allies would not reach Paris before mid-August, he could use the extra time to recruit and train more combat troops. He would than be able to concentrate his forces around Paris and meet the advancing Allied armies with numerical superior forces. But this strategy meant that large parts of France would be lost to the enemy with very little or no resistance at all. This would look very bad to the French people and Napoleon still very much needed to get the population behind him.

His second option was to attack the Allied troops in the Netherlands with the forces he already had. The disadvantage of this strategy was that he could only bring about 125.000 troops in the field against more than 200.000 Allied troops commanded by the Coalition's best generals. The possible advantages of a victory over these generals however were huge:

An Allied defeat would make the Seventh Coalition shake on its foundations. The French would rally as one person behind Napoleon and this would give him the much needed freedom of action. There was also a very real possibility of a pro-French revolt in the Netherlands once the Allied powers in those regions were defeated. This would give Napoleon an extra source of manpower: there were large numbers of seasoned veterans of the former Napoleonic armies in the Netherlands and lots of new recruits.

Wellington's defeat would probably provoke the fall of the British Tory government. With a new Whig government it would be much easier to talk about peace.

A French victory in the Netherlands would secure the north-north-east border so Napoleon would be able to wheel to the right and attack, reinforced by his observation Corps, the enemy at his eastern border.

Napoleon chose the offensive strategy. While he would attack in the Netherlands with the "Armée du Nord", his observation Corps would guard the French borders.

The "Armée du Rhine" of General Jean Rapp (23.000 troops) was in position to stop the Austrians of Schwarzenberg once they started their advance.

The 8.400 soldiers of General Lecourbe's "Armée du Jura" faced Bachmann's 37.000 Swiss.

Marshal Suchet's 23.500 strong "Armée des Alpes" was ready to protect Lyons against the Austrian-Piedmonts army.

Marshal Brune's "Armée du Var" (5.500) observed the Neapolitan army of Onasco.

In the rebellious department of the Vendée, General Lamarque and his 10.000 troops were supposed to end the uprising or at least to keep it under control.

Napoleon sent two armies in the field against the Spanish-Portuguese threat. The "Armée des Pyrinees Orientales" (7.600) de Decaen at Toulouse and the "Armée des Pyrinees Occidentales" (6.800) de Clausel at Bordeaux.

The minister of war, Marshal Davout disposed of 20.000 troops to protect Paris with.

Early in June 1815 the first preliminary orders were given. Soon after this, the first, very concealed, troop movements to the "Belgian" border commenced.

WAR OF THE THIRD COALITION

Introduction

The Grande Armee - 200,000 strong - was assembled in camps all along the channel coast in preparation for the great invasion against Britain. But the French navy could not lure away the British fleet. Unable to secure temporary control of the English channel to ensure his army's safe crossing, and facing the newly concluded Third Coalition of Britain, Austria and Russia (concluded in April 1805), Napoleon was forced to abandon his plans to invade Britain. On 25 August 1805, the Grand Armee of 7 Corps, was ordered to march south towards the Danube and then east on Vienna.

In the meantime, the allies planned a 3 pronged attack against Napoleon - the British would recapture Hannover - an Austrian army (with Russian support) under General Mack would invade Bavaria (a French ally) - and an Austrian army under Archduke Charles would liberate Northern Italy and drive into southern France. In addition, an invasion against Naples and raids on the Dutch coast were planned. But the allies had seriously underestimated Napoleon...

Ulm and "The Unfortunate General Mack"

On 10 September, Mack invaded Bavaria and occupied Ulm with his 85,000 men. He then waited for his Russian reinforcements to come up. The Grande Armee's dazzling march was totally unexpected. It was only on 30 September that Mack realised he was in danger of being encircled. A series of clashes were fought - at Wertingen, along the River Iller, at Hasslach and at Elchingen. By 15 October, Mack was almost completely surrounded.

Hoping to win time for 50,000 Austro-Russian reinforcements under Kutusov to arrive, Mack opened negotiations with the French. When it became clear that the Russians were still far away, Mack finally surrendered his army of 30,000 on 20 October.

This great victory was achieved, not through a major battle, but through a legendary manoeuver - the inspiration for the blitzkrieg.

The next stage of the campaign was basically a pursuit by the French of Kutusov's force. Kutusov managed to skilfully escape the clutches of the French until he linked up with Buxhowden's 30,000 Russians on 20 November - near Olmutz. On 23 November, Napoleon - now with only 53,000 troops under his direct command - called a halt at Bruenn (present day Brno). By Austerlitz, Napoleon - reinforced with Bernadotte's and Davout's corps - managed to field an army of around 73,000 men.

Austerlitz

The Battle of Austerlitz, 2 December 1805, was one of Napoleon's masterpieces. Though outnumbered, Napoleon managed to rout the Austro-Russian army - thereby causing the destruction of the Third Coalition.

Through a series of deceptions, Napoleon tricked the Allies into thinking that his army was weak and could easily be swept aside. The Allies fell for his trick and were lured to turn the French right flank. The allied attack began at dawn - although the battlefield was shrouded in mist.

When Napoleon judged that the Allies were fully committed on his flanks, he gave Soult the order for the Allied centre (located on the Pratzen Heights) to be stormed. The time was 9am - and the legendary "Sun of Austerlitz" revealed itself through the mist. By 11am, the French controlled the Pratzen Heights.

Meanwhile, a fierce cavalry battle was taking place on the French left flank (Lannes) - with the Allies getting the worst of the exchange. When Lannes judged that the time was ripe, he ordered forward his infantry - which advanced admirably despite terrible losses. By midday, the Allies were giving way.

Back on the Pratzen, desperate Allied counterattacks made no headway. Finally, the Russian Imperial Guard Corps under Grand Duke Constantine was thrown into the fray - the last roll of the dice. The Russian Imperial Guard - totalling 3000 Grenadiers and 15 squadrons of Guard Cavalry - assaulted the Pratzen, routing the 4th Ligne and 24th Legere Regiments. The gap in the French line was filled by the French Imperial Guard chasseurs-a-cheval and the grenadiers-a-cheval. A fierce melee took place between the French and Russian guard cavalry. Napoleon ordered the Mamelukes and 2 more squadrons of chasseurs-a-cheval into the fray.

Suddenly, the Russians retired - the French had the upper hand, by a razor thin margin.

With control of the centre, Napoleon ordered his troops to wheel right in order to destroy the over-extended Allied left wing. This was the beginning of the end for the Allies. Their troops began to give way - soon they were in full retreat. The only escape route for the Allies was southwards, and many fled across the frozen Lake Satschan.

(The story of French batteries firing on the frozen lake to break the ice and thereby drown the retreating Allies has now been cast into doubt.)

Austerlitz cost the French 9000 casualties. The Allies suffered 27000. Napoleon's Order of the day read as follows:

"Soldiers, I am pleased with you! You have, on this day of Austerlitz, justified all that I had expected from your courage, and you have honoured your eagles with immortal glory. In less than 4 hours, an army of 100,000 men, commanded by the Emperors of Russia and Austria, has been cut down or scattered. Such enemy as escaped your bayonets have drowned in the lakes.

40 colours, the standards of the Russian Imperial Guard, 120 pieces of artillery, 20 generals and over 30,000 prisoners are the result of this day - to be for ever celebrated. That such vaunted infantry, so superior in numbers, could not resist your charge, proves henceforth you have no longer any rivals to fear. Thus in 2 months, this Third Coalition has been overthrown and dissolved. Peace cannot now be far away...

Soldiers, when everything necessary for the happiness and prosperity of the motherland has been accomplished, I will lead you back to France: there you will be the object of my tenderest solicitude. My people will greet you with joy, and it will suffice for you to say, 'I was at the battle of Austerlitz', for them to reply: 'there is one of the brave.'"

2 days later, an armistice between France and Austria was concluded. Russian armies were in full retreat, and the Tsar sent Napoleon the following message:

"Tell your master (Napoleon) that I am going away. Tell him that he has performed miracles...that the battle has increased my admiration for him; that he is a man predestined by heaven; that it will require a hundred years for my army to equal his."

Battle of Austerlitz

Introduction:

It was before dawn on December 2, 1805--the first anniversary of Napoleon's coronation as supreme ruler. The armies of three emperors--Napoleon I of France, Francis I of Austria and Tsar Alexander I of Russia--would meet in the day that followed

Dawn: The Allied Assault

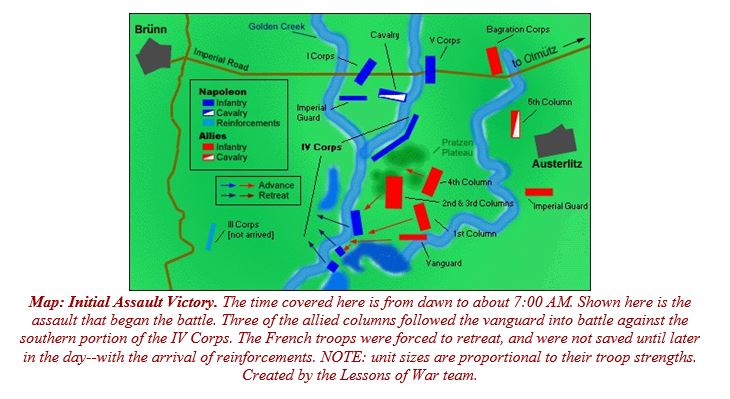

At the break of day, the vanguard (or lead elements) of the allied 1st Column burst upon the French encampments in the southwest corner of the battlefield.

Soon after 7:00 in the morning, the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Columns--three of the four stationed on the Pratzen Plateau--descended into the valley next to Golden Creek. Though one division of Napoleon's IV Corps resisted heavily, the French faced a much superior force and gave way. By 10:00 AM, the allies had nearly broken through enemy lines--and might have, had not the French III Corps arrived just in time to salvage the situation.

Napoleon's 'Lion Leap' Through the Fog

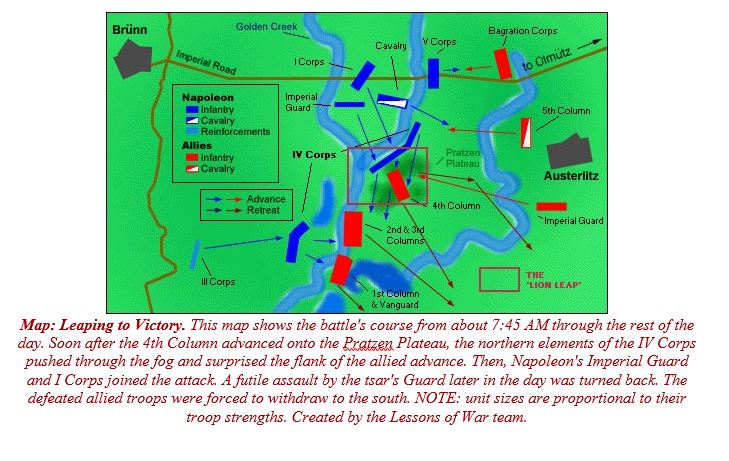

At about 7:45 AM, just after the allied columns started in motion down the slopes of the plateau, Napoleon executed an extraordinary maneuver known now as the "lion leap": the rest of the IV Corps surged through the morning's thick fog and assailed the right flank of the Allied advance.

Illustration: The Lion Leap. As the 4th Column was advancing to engage the southern detachment of the IV Corps, Napoleon used the rest of that corps to make a devastating flanking assault. Created by the Lessons of War team.

His troops emerging from the haze and the sun rising over Austerlitz, Napoleon beheld his army at the pinnacle of its success and glory.

Though startled by the unexpected--and unseen--appearance of French forces, the Allies recovered sufficiently to organize a defense. The 4th Column, still on the plateau, began marching into the valley; and elements of the 2nd Column were sent back from the front to defend the hilltop.

Clinching Victory

The allied reinforcements were defeated after a bitter fight. Now, the French assault on the flank received fresh reserves of its own, as the I Corps joined the divisions of the IV Corps. Napoleon now established his command post on the peak of Pratzen Plateau to observe the destruction of the Austrian and Russian armies.

The situation for the allied columns in the Golden Creek valley deteriorated: they were now pinned down by French forces from two sides. In one last bold but fruitless attempt at relief, the Russian Imperial Guard charged up the plateau but was turned back. Avoiding total ruin, the allied troops retreated to the south.

1806 - Jena and Auerstaedt

Introduction

In the aftermath of Frederick the Great's great military victories, Prussia's military reputation was unrivalled. Unfortunately, reputations do not win wars. Although the Prussian army was well trained in the tactics of the day, its failing lay in the fact that the Prussians did not have a military leader to match Napoleon - the greatest military mind of the age. To make things worse, Prussian commanders could not even agree on a plan of action. Lack of an overall plan, combined with command and control failings would lead to Prussia's downfall - however, no one could have predicted the swiftness of that defeat.

Prelude to War

Austria had been defeated at Austerlitz in 1805. Although Prussia had been tempted to enter into the war of the Third Coalition against France in 1805, it had not done so in the hope of gaining French-occupied Hannover as a concession. However, the Austrian defeat left Prussia isolated in Central Europe. Sensing opportunity, Napoleon demanded and obtained the Prussian territories of Cleves, Ansbach and Neuchatel. In return, Napoleon offered Prussia Hannover - but the treaty had not been ratified. More humiliation followed - the formation of the Confederation of the Rhine threatened Prussia's control over German affairs. The final straw was Napoleon's offer of Hannover to Great Britain in return for peace. Napoleon had gone too far - Prussian honour was at stake and the army was mobilised on 10 August 1806.

Opening Moves

Valuable time was wasted as the Prussian high command could not decide on a plan of action. After several weeks of discussion, it was finally decided that the Prussian army would strike towards Stuttgart in order to drive a wedge between the dispersed French corps and threaten their lines of communications. But it was too late, by 5 October, the Prussians learnt that Napoleon had already seized the initiative and was advancing northward with 6 Army Corps and the Imperial Guard through the Thueringerwald (a heavily wooded and hilly area) towards Jena.

The Prussians had 2 divisions posted near Schleiz (under General Tauentzien) and Saalfeld (under Prince Louis Ferdinand). These were easily brushed aside by the French I and V Corps respectively as they came out of the Thueringerwald. At Saalfeld on 10 October, Prince Louis was killed in personal combat with Quatermaster Guindet of the French 10th Hussars. The Prussians fell back and were ordered to concentrate around Erfurt/Weimar area.

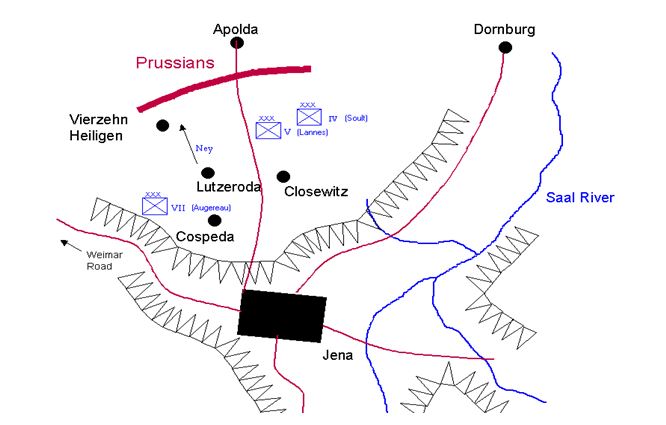

The French "battalion square" formation swung 90 degrees westwards towards the Prussian concentration. On 13 October, Lannes V Corps discovered 30,000 Prussian troops around Jena. Napoleon sent orders for all Corps to concentrate there by 14 October. To cut off the Prussian line of retreat, Davout's and Bernadotte's Corps were ordered to Naumburg and Dornburg respectively.

The Battle of Jena

The battle began in the early morning of 14 October. The battlefield was on a ridge (the Landgrafenberg) northwest of Jena. Lannes V Corps was ordered to attack at 6.30am in order to win more space on the ridge for the other French corps converging on the battlefield. Lannes' attack was spearheaded by Suchet's 1st Division on the right, and Gazan's 2nd Division on the left. These initial moves were centred around the villages of Cospeda, Luetzeroda, Closewitz and Vierzehnheiligen.

In the meantime, on the French right flank, Soult's IV Corps made contact with the Prussians in the area between Closewitz and Roedigen. A Prussian attack led by Lt General von Hoeltzendorff was repulsed by Soult's Corps. Augereau and his VII Corps were working their way around the Prussian left flank along the Jena-Weimar road in the valley below.

Ney soon arrived on the scene with an advance guard of 3,000 men comprising 2 squadrons of light cavalry and 2 infantry battalions. Without waiting for the rest of his Corps to come up, the fiery Alsatian charged into the fray to the left of Lannes V Corps and towards Vierzehnheiligen. But Ney had overextended himself and soon found himself cut-off as hordes of Prussians bore down on his position. The Prussian commander, Prince Hohenlohe, had ordered a general assault by 45 squadrons of cavalry and 11 battalions of infantry. Seeing Ney's predicament, Napoleon ordered Lannes to make a fresh assault to link up with Ney. Augereau was ordered to cover Ney's left flank. Lannes Corps and the advancing Prussians made contact around Vierzehnheiligen and Ney's survivors were pulled out. Meanwhile, Hohenlohe's troops floundered around Vierzehnheiligen and started taking heavy casualties from French artillery.

At around 12.30pm, Napoleon judged that the "battle was ripe". VII (Augereau's) and IV (Soult's) Corps were ordered to pin down the Prussian flank, while V (Lannes') and VI (Ney's) Corps punched through the centre. In the face of repeated French assaults, finding both flanks in danger of being turned, and with no sight of reinforcements, Hohenlohe ordered a general withdrawal. At this point, Murat's cavalry was unleashed and the withdrawal turned into a rout.

The French had lost 5,000 men - the Prussians: 10,000 dead, 15,000 prisoners, 34 colours and 120 guns. All this while, unknown to Napoleon, another desperate battle raged on at Auerstaedt - 8 miles to the north.

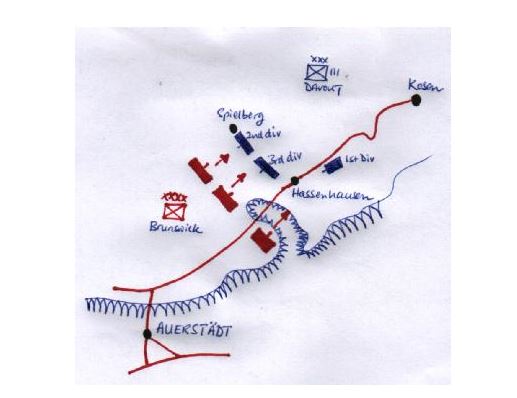

The Battle of Auerstaedt

This battle happened quite by chance. Davout's III Corps (around 29,000 men) was following orders to cut off the Prussian line of retreat from Jena. At the same time, the main Prussian army under the Duke of Brunswick (63,000 men) was moving northwards to link-up with Wuerttemberg's Reserve Corps of 15,000 men at Halle. These 2 forces were destined to meet at Auerstaedt on 14 October 1806.

First contact was made at 7am when cavalry detachments from both sides stumbled into each other in the thick morning fog. The French, outnumbered, fell back and their leading infantry regiments formed square to repel the Prussian cavalry. Initial Prussian attacks (led by the hot-headed Bluecher) were made almost solely by cavalry. The bulk of the Prussian infantry and artillery were still in the rear. Without infantry and artillery support, the cavalry charges against solid infantry squares did not succeed.

However, by mid-morning, the bulk of the Prussian forces were on the field. The fighting centred around the villages of Spielberg and Hassenhausen. Davout took a risk and placed 2 Divisions around Spielberg leaving only the 85th Line Regt to watch Hassenhausen. Fortunately for him, the Prussian main assault was directed against Spielberg. Fierce fighting developed around these 2 villages. At one point, the hopelessly outnumbered 85th Line broke and fled - but was rallied by Davout himself and pushed back into the line.

During the fighting around Spielberg, the Prussian commander, the Duke of Brunswick, was killed. This left the Prussian army in the hands of the inexperienced King Frederick-William III - who was overawed by the erroneous belief that he was facing Napoleon in person.

By 11am, Davout's 1st Division arrived on the battlefield. These were directed to reinforce the exhausted troops at Hassenhausen. Prussian assaults were repelled.

By noon, the French - initially outnumbered 2:1 - began their advance and forced the Prussians to retreat. The toll was 10,000 Prussian dead and 3,000 prisoners at a cost of 7,000 French casualties. In recognition of Davout's feat of arms, Napoleon caused the following Bulletin to be published:

"On our right, Marshal Davout's Corps performed wonders. Not only did he contain, but drove back and defeated, for over three leagues, the bulk of the enemy's troops, which were to have debouched through Kosen, This marshal displayed distinguished bravery and firmness of character, the first qualities in a warrior."

Aftermath

The main Prussian armies had been defeated. Remaining Prussian forces were scatterred all across Prussia. The remainder of the campaign was basically a mopping-up operation. By 27 October, the French entered Berlin - with Davout, the hero of Auerstaedt - at their head.

Although almost the whole of Prussia lay in French hands, Prussian forces east of the Oder river continued to resist - waiting for their Russian allies. The stage was set for the terrible winter campaign of 1806-1807.

War against Austria 1809

Introduction

The 1809 Campaign was, militarily, only a marginal victory for Napoleon. Austrian troops under Archduke Charles acquitted themselves extremely well on the fields of Aspern-Essling and Wagram. Napoleon's narrow victory at Wagram would be his last. Even then, it was not satisfying. Napoleon was quoted after Wagram saying: "War was never like this, neither guns nor prisoners. This day will have no result." In fact, the French sufferred more casualties and lost more Eagles at Wagram than the Austrians.

Preparations for War

French reversals in the Peninsular, British urging, and the desire to revenge the humiliating defeat at Austerlitz led the Austrians to begin preparations for war. The target date - Spring 1809. Napoleon, having caught wind of Austrian preparations, secured a promise for Russian intervention on the French side in case of war with Austria. Satisfied with Russian assurances, Napoleon transferred 200,000 troops from Germany to Spain in Autumn 1808 to deal personally with the Spanish problem. But news of court intrigues caused Napoleon to rush back to Paris in January 1809. In Paris, Napoleon learnt not only of court intrigues, but also received confirmation that the Austrians were seriously mobilising their forces for war. Austrian plans called for an invasion of Bavaria, with secondary operations in Poland and Northern Italy.

The Imperial Guard was recalled from Spain and orders were sent out for French forces to concentrate at Ratisbon, Germany. On 10 April 1809, Austrian forces - 6 Corps strong - crossed into Bavaria. The war had begun.

Austrian Invasion of Bavaria

The Austrian attack on Bavaria was a pincer movement. I and II Korps crossed into Bavaria north of the Danube. III, IV, V, VI and 2 Reserve Korps entered Bavaria between Passau and Braunau.

Davout, with III Corps positioned around Regensburg, was caught in the middle of the pincer. When Charles learnt of this, he ordered III and IV Korps to close the pincer around Davout. II Reserve Korps and V Korps were ordered to move to the Abens river in order to protect the left flank of III and IV Korps. VI Korps was ordered to secure the entire army's left flank.

Davout was ordered to retire from his threatened position at Regensburg. After an engagement at Teugen and Hausen with elements of Austrian III and IV Korps, Davout broke through the jaws of the pincer. Napoleon then ordered the Bavarians, Wuerttembergers and a provisional French Corps under Marshal Lannes to attack the Austrians across the River Abens. The Austrian V Korps was pushed back to Landshut.

Napoleon then realised that the Austrian main force was pursuing Davout in the north. He turned his troops facing the Austrian V Korps and marched north. This ended in the Austrian defeat at Eckmühl on 22 April. The Austrians retreated into Bohemia. Defeated, the Austrian army was unable to prevent Napoleon from pushing on and capturing Vienna on 13 May 1809. However, this was a hollow victory. Napoleon still had to deal with the Austrian army - 100,000 strong - still hovering somewhere to the north of Vienna.

Aspern-Essling, 21-22 May 1809

Although his troops numbered only 80,000, Napoleon was impatient and wanted to inflict a quick defeat on Austria. The memories of Austerlitz were reinforced by the Austrian reversals earlier in Bavaria. A decision was made to cross the swollen Danube to the Lobau island and then on to Mühlau. French troops began crossing to Lobau island on 19 May 1809. By 21 May, French forces were positioned between the villages of Aspern and Essling - a front approx 2 km in length.

Charles had decided to let the French cross the Danube in order to defeat it in the field. If defeated, the French army with the river to its back, would be easily destroyed. In accordance with this plan, Austrian forces were arrayed in a semicircle around the French.

The Austrian assault - 3 Korps strong - began on the morning of 21 May, with the main thrust on its right flank - against the village of Aspern. At this point, the French only had 3 infantry divisions and several cavalry brigades and the bridge across the Danube was broken. The French position looked perilous but was strongly anchored on the 2 villages of Aspern and Essling - with the cavalry covering the centre.

The initial Austrian attacks on Aspern were hasty and uncoordinated and made little headway against the French. However, by late afternoon, repeated assaults and the weight of Austrian numbers were beginning to tell. Personal intervention by Charles inspired the Austrian troops to make a final all out assault, and Aspern was taken at 6.30pm. Fresh French troops were ordered to retake Aspern and by nightfall, neither side could claim full control of the ruined village.

While the battle raged on in Aspern, French cavalry charged the Austrian centre in an attempt to relieve the pressure on the embattled village. These charges were easily repulsed by Austrian infantry deployed in battalion masses - muskets bristling on all sides.

Austrian troops also made several assaults on Essling. These were largely uncoordinated and failed to make headway - particularly against the massive stone granary.

French reinforcements crossed the Danube during the night and were available for action the next day. Napoleon planned a massive assault against the Austrian centre. To prepare for this, he ordered the immediate recapture of Aspern - in order to secure his left flank. At the same time, Austrian assaults on Essling were repulsed. By 7.00am, both Napoleon's flanks were secure and his move against the Austrian centre could proceed.

The French assault would be by 3 divisions supported by cavalry and artillery under Lannes' command. In the face of this and several French cavalry charges, the Austrian line began to waver. But Charles' presence and personal intervention kept the line steady. In the meantime, Austrian artillery rained death and destruction on Lannes assault columns. Taking heavy casualties - and without reserves - the French were forced to retire. Napoleon's gamble had failed.

Meanwhile, Austrian assaults on Aspern and Essling continued unabated. By 3pm, both villages were taken and preparations were made for a massive thrust against the French centre. A grand battery of 200 guns was positioned along the front centre of the Austrian army and began bombarding the French centre. In a desperate attempt to stave off defeat, Napoleon launched his cavalry against the Austrian centre. Under cover of this charge, French troops began a disordered retreat across the Danube.

Although he would later claim a victory, Napoleon had sufferred his first major defeat. However, his army was still intact and more troops were on the way from Germany. By early July, Napoleon had assembled an army twice as strong - 190,000 men. The Austrians could only field 137,000 men and Charles was urging his brother, the Archduke John, to hurry back with his 2 corps of troops in Northern Italy: "The battle here on the Marchfeld will determine the fate of our Dynasty."

Wagram, 5-6 July 1809

Napoleon had learnt his lesson. The next crossing was well-planned. First, a deception that he intended to cross again at Mühlau. Then, well constructed bridges were placed across the Danube to the east, near Gross-Enzersdorf.

The main Austrian force was concentrated on a height known as the Wagram. Here were massed 2 Austrian corps. 3 corps covered the right flank, and 1 corps on the right. The entire front stretched some 20km. In addition, 2 corps were assigned to fight a delaying action between the Danube and the main Austrian position.

By 6pm on 5 July, the French were in position facing the Austrians. Instead of waiting, Napoleon issued orders for an immediate assault by 4 corps on the main Austrian position on the Wagram. The assault began at 7pm heralded by a massive artillery bombardment. A desperate struggle for possession of the Wagram began. Under heavy assault, it looked as if the Austrian I Korps holding the right of the Wagram would break. Once more, Charles' personal efforts steadied the line and led the Austrian counterattack against the exhausted French. The crisis was over, the French retreated back to their start line.

On 6 July, the French plan was to launch a pinning attack against the Austrian centre and outflank their left. On the other hand, Charles realised the weakness of the French left. The main Austrian attack would go in against the French left in an attempt to cut them off from the Danube and then take the French army in the rear.

The day began with an Austrian advance on the French left by IV Korps. However, the failure of III and VI Korps to show up at their start line on time led Charles to order IV Korps back to the start line. This caused Napoleon some concern as it was thought that Archduke John had finally shown up with his 30,000 men. The failure of III and VI Korps to show up on time had compromised the Austrian plan and lost them the element of surprise.

Meantime, I Korps was ordered to advance against the French in order to pin down their left flank. The unsanctioned abandonment of the village of Aderklaa by Bernadotte made the Austrian advance plain sailing. Napoleon was furious and ordered Massena to retake Aderklaa at all costs - but to no avail.

The Austrian VI Korps was now on its way against the French rear. Napoleon was concerned as this position was weakly held by 1 French division. Notwithstanding that VI Korps broke through the French left rear, lack of initiative of the commander on the ground prevented the success from being exploited. Instead of advancing against Napoleon's rear, VI Korps sat down to wait for III Korps to come up to its position. Napoleon immediately ordered a cavalry charge and artillery bombardment against the Austrian line in order to cover Massena's move south to meet the threat posed by VI Korps.

Napoleon then launched Davout against the Austrian left flank.

Notwithstanding a massive artillery bombardment followed by desperate infantry and cavalry battles, the French were unable to break the Austrians.

In a final desperate move to break the Austrians, Napoleon ordered a general assault all along the line. Macdonald, commanding the French centre, formed a massive square of 30 battalions to advance against the Austrian centre. The Austrians poured all their fire into this lumbering square causing massive casualties. Within an hour, out of 8,000 men who began the advance, only 1,500 remained standing.

However, French attacks on both flanks were gaining some measure of success and the Austrian troops on the Wagram were already exhausted after a whole day of almost continuous fighting. Furthermore, there was no sight of Archduke John's 2 corps. Anxious to save his army, Charles issued orders for a phased withdrawal. This was carried out in good order.

Aftermath

After several rearguard actions, a ceasefire was agreed on 11 July. The defeat caused Charles to resign his command in bitterness. An armistice was signed in October. Austria lost much territory and had its army limited to 150,000 men. Although Austria had been defeated, Napoleon henceforth would show great respect for the fighting qualities of the Austrian soldier.

INVASION OF RUSSIA (1812)

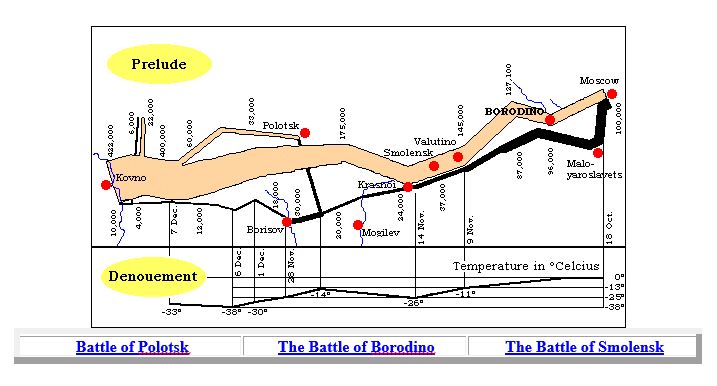

From the Niemen to Vitebsk

When Napoleon first set foot in Russia, he had no expectation of marching to Moscow. His avowed aim was to force the Russian armies into major battle at the earliest possible moment somewhere in the frontier region, ideally in scattered detachments. No specific target was laid out, but it was thought that the Russian army would be engaged in the vicinity of Vilna, fifty miles inside the Russian border.

The Russian army had decided, however, on a tactic of strategic retreat, whereby Barclay's First West Army would draw Napoleon to Drissa, allowing Bagration's Second West Army to strike the Grand Army from the flank. The effect of this dispersion was to allow Napoleon to drive between the two Russian armies, and penetrate deep into the right center of the Russian lines.

Napoleon pursued Barclay to Vitebsk on the Duna River, while the French divisions led by Marshal Davout sought to block Bagration's path north to join with Barclay. Seeing that he would be without support, Barclay abandoned his position at Vitebsk, and the two Russian armies made haste by converging courses to set up new defensive positions at Smolensk.

As they fell back, though, they pursued a strategy of stripping the land of food and fodder, making the invaders dependent on long supply lines that would grow more vulnerable as they lengthened.

Vitebsk to Smolensk

On the 10th of August Napoleon gave the order to advance from Vitebsk where he had remained only fifteen days. His plan was to move 185,000 men around the left flank and to the rear of the Russian armies in a counter-clockwise sweep, engaging the Russian armies separately and attacking Smolensk from the south.

The necessity of organizing liberated Lithuania, of setting up hospitals and supply depots, of establishing a central point for recuperation, defense, and subsequent departure on a line of operation which is growing longer and longer everyday--shouldn't all this make us decide to stop here on the border of old Russia?

Do you think I have come all this way just to conquer these huts?

--Napoleon Bonaparte, 28 July,1812

Siege of Smolensk

For more than two months Napoleon's armies had sought to bring the Russians to a decisive battle. Napoleon believed he had them pinned down at Smolensk where the Russian generals, Barclay and Bagration, had brought their forces together. When the Russian armies were seen, nearly one hundred and twenty thousand men, marching across the right bank of the Dnieper River, Napoleon hoped their intent was to deploy their forces beneath the city's walls to wage the battle so long awaited.

On the morning of the seventeenth the Russians were seen in full retreat on the eastern road to Moscow. Napoleon responded with a full-scale assault on the city. His flamboyant marshal Murat opposed such a violent action, especially since the Russians were withdrawing on their own initiative. But the city was stormed and fighting ensued with the Russian rearguard, left behind to defend and evacuate the city as the main armies withdrew. The entire city was set on fire as a barrier to French pursuit. A part of the French army was able to catch the rearguard of Barclay's army in a bloody encounter at Valutino, on the plateau east of Smolensk. But the Russians had again evaded the Grand Army and left Smolensk a smoldering ruin for the French to inhabit.

Smolensk to Borodino

At Smolensk Napoleon paused to take stock of his situation. Sickness and desertion had thinned his army's ranks to 185,000 men by the time he'd reached Smolensk; the heavy marching and fighting of the last few days had cost him 25,000 more. It seemed prudent to consolidate his forces here behind the river lines of the Dvina and the Dnieper, to wait out the winter while he made ready for a new campaign in 1813. He had by now outrun his supply depots, overextended his lines, and 280 miles separated him from the next major town to the east, which was Moscow.

Nonetheless, Napoleon decided that Russia would not surrender and Alexander would not negotiate until there had been a decisive battle. Smolensk was at the junction of the main roads to St. Petersburg and Moscow--twenty-nine days' march from the first of these capitals, fifteen from the second. On 25 August, 1812 the French left Smolensk, following the Russian armies on their retreat along the road to Moscow.

The Russian general Barclay's tactics of strategic withdrawal had been intrinsically sound for the circumstances, but the Russian aristocracy vehemently denounced him for "leading the French straight to Moscow." Yielding to the outcry, Tsar Alexander abruptly replaced him with the aged general Kutusov. Kutusov knew that he would now be expected to stand and fight.

Preparation for Battle

The Russian army under Kutusov drew up at a site south of the village of Borodino, on a ridge intersected with ravines and behind the Kolotcha, a tributary of the Moskowa, the river which flowed through Moscow seventy-two miles to the east. Napoleon's Grand Army arrived on the hills facing the Russians on 5 September with 130,000 men to face 115,000 Russians. This was the battle Napoleon had wanted, but the battlefield was not one he would have chosen. The country was wooded and therefore unsuitable to the cavalry and the flanking movements by which Napoleon was accustomed to defeating the enemy. The Russians had also been afforded the time to dig in on sloping ground; their main batteries were protected by turf redoubts and would be difficult to capture.

The Russian lines stretched north and south for two and a half miles from Borodino to the village of Utitza, on the Old Smolensk-Moscow road. On the Russian right Barclay with 75,000 men held high ground protected by giant earthworks known as the Great or Raevsky Redoubt, then came a dip in the land; beyond the dip three more redoubts--the Bagration Fleches--and finally the wooded ground above Utitza.

Napoleon's strategy was a simple one. His stepson Eugene would attack the village of Borodino, as though the main French thrust was to come on the Russian right. In fact, it would come at the Russian center and the left, where the Russian lines were weakest. There Marshal Davout would attack Bagration, while the Polish Prince Poniatowski's cavalry, using the Old Smolensk-Moscow road, would try to maneuver behind the left flank of the Russians, driving the whole army to the right and into the ravine of the Kolotcha.

On the evening before the battle, Napoleon asked his aide-de-camp Rapp if he expected a victory. "Without any doubt," Rapp replied. "But a bloody one."

Battle of Borodino, 7 September 1812

At half past five on the morning of September 7, Napoleon ordered his French batteries to begin firing. By ten o'clock Napoleon's original plan had been overtaken by events. Eugene had done better than expected, capturing Borodino, bringing up guns, and pounding the Raevsky Redoubt. But Poniatowski had fared less well. Though he had battered the Russian left--General Tuchkov was dead and Bagration dying of wounds--he was unable to take the Bagration Fleches from behind.

In the Aftermath

It was clear then that the remainder of the battle would consist of gun duels, frontal attacks, and hand-to-hand fighting. By midday, the center of action was shifting to the Raevsky Redoubt, a fortified emplacement of twenty-seven guns. The fighting was so fierce there, according to one eyewitness, that "the approaches, ditches, and interior all disappeared under a mound of dead and dying, an average six to eight men piled on top of one another.

It was in the late afternoon that Eugene from the north, Ney and Murat from the south, launched a combined attack on the Raevsky Redoubt. This time they succeeded in capturing it and turned round the guns on the Russians retreating over the ravines to the east. The French had taken this battlefield but they were too decimated to pursue the Russian armies any further as they withdrew towards Moscow.

The losses at Borodino were enormous and without proportionate results. The Russians had fought and died with stubborn heroism, 44,000 dead and wounded. The French had lost 33,000 men, including forty-three of their generals who had been killed or wounded. Arithmetically, and in the sense that the road to Moscow now lay open, Borodino was a French victory. But it was far from the crippling, decisive victory on which Napoleon had been trusting his campaign. It was the most terrible battle Napoleon had ever fought.

The Grand Army was left with only 95,000 men to continue its march toward Moscow. They met little resistance as they moved through the towns of Mozhaysk and Krymskoie. But the Russian army had not been vanquished by its losses, resuming its evasive tactics and withdrawing to a base south of Moscow. Napoleon sent an urgent message to the Duke of Bellano who had remained behind with reserves in Poland, requesting that all manner of reinforcements be dispatched immediately to Moscow.

Entry into Moscow

On the 13th of September, almost three months after entering Russia, the main body of the Grand Army reached the outskirts of Moscow and climbed the western hills to gaze at last, after hundreds of miles of empty spaces and burned-out ruins, on the gilded roofs and domes of a city rising from the middle of a fertile plain.

At three in the afternoon, Napoleon and the Imperial Guard arrived before the Dragomilov Gate, expecting to be met by a deputation of the city elders bearing the municipal keys and other tokens of submission. In fact, most Muscovites had been ordered to evacuate by the governor Rostopchin. Of 250,000 residents, only 15,000 remained. The French found no delegation ready to parley with them, a fact that troubled Napoleon although he dismissed its significance. As the Grand Army rode through an untended gate, their boots and hooves echoed through the city streets, deserted save for a few convicts and wounded soldiers.

Napoleon took up residence in the Kremlin, from whence he sent out overtures to Tsar Alexander for terms of peace. Now that he had defeated the Russians and occupied their capital, he was sure that they would act like reasonable Europeans and meet his demands. Perhaps he and Alexander could even be allies again.

Moscow in Flames

The night of 15 September fires broke out all over Moscow. The French had to fight them with buckets of water, as hoses and pumps had been removed on orders from Rostopchin. Many more fires were ignited the next day, and the French soon found out that Rostopchin had armed a thousand released convicts with fuses and gunpowder and instructed them to burn Moscow to the ground. The French could not check the raging fires, and over the next four days four-fifths of the city of domes had been destroyed.

As at Smolensk, the French were appalled and daunted by such uncompromising determination and sacrifice by the Russians, willing to turn their own capital into a blackened ruin. Napoleon wrote to Alexander, seeking some form of accommodation: "If your Majesty still conserves for me some remnant of your former feelings, you will take this letter in good part."

For five weeks Napoleon waited in vain in the ruins of Moscow for an answer from St. Petersburg. His original plan had been to winter in Moscow where his soldiers would be comfortable, with plenty to eat and drink. But as supplies of food and forage diminished and the Russian army encamped to the south at Tarutino grew in strength, Napoleon decided that there was no point any longer in holding on to his increasingly precarious position in an isolated city 550 miles inside enemy territory. He proposed instead to take the Grand Army on a wide circuit south and west through fertile and unspoiled land to the area of Minsk-Smolensk-Vitebsk, where he would set up winter quarters and prepare for a campaign against St. Petersburg in 1813.

Napoleon intended to begin the evacuation on the 20th of October. On the 15th three inches of snow fell over the black ruins of Moscow. On October 18 Murat's advance guard lost 2,500 men in a surprise attack by the Russian army at Vinkovo south of Moscow. Napoleon pushed the date forward by a day, and on 19 October the first units of the Grand Army, after a stay of 35 days, filed out of the city. The immense crawling procession of 90,000 infantry and 15,000 cavalry, with carriages, wagons, artillery, pack animals, and useless booty of all kinds crowded the westward roads leaving Moscow.

Maloyaroslavets

From Moscow Napoleon first struck south along the Old Kaluga Road, then veered west by secondary roads intending to slip around Kutuzov's left flank to the important junction of Maloyaroslavets, from where a variety of routes led through untouched country to Smolensk. Advance troops of the French and Russian armies converged almost simultaneously on Maloyaroslavets on 24 October, where they engaged in a fierce eighteen-hour battle that cost 10,000 men. Kutuzov meanwhile, divining Napoleon's strategy, assembled his main army a mile to the south, resolved to give battle the next day rather than let the French break through to Kaluga.

Though the Russians were eventually driven from the town, Napoleon was forced to reconsider whether his 63,000 troops could achieve a breakthrough against more than 90,000 Russians. On October 26 Napoleon ordered the Grand Army to break contact and turn back north to the main Smolensk road that had been stripped bare during the advance to Moscow. The Grande Armee reached the Smolensk road at Mozhaysk, then turned west through an all-too-familiar landscape. On the 29th the French troops were forced to retrace their steps over the fields of Borodino, where they witnessed the horrific sight of the entire plain covered still with tens of thousands of unburied corpses.

Kutuzov had not thought the French would give up there southern objective so easily. As he reported to Alexander, the brush at Maloyaroslavets on 24 October now proved to be "one of the most significant days of this bloody war," for if the battle of Borodino showed that Napoleon could not defeat the Russians, then the encounter at Maloyaroslavets ensured not just that he was going to lose the war, but that his loss was going to be catastrophic.

Retreat through Russia

Kutusov's strategy was to avoid a major engagement with Napoleon's army on a battlefield such as at Borodino, and merely to interpose his army between Napoleon and the fertile, unspoiled lands to the south of the main road, leaving hunger, fatigue, sickness, and the onslaught of winter to do what his armies could not. Any stragglers or foragers off the main road were to be cut down by flying columns of Cossacks and bands of peasants, restricting the area from which Napoleon could draw his supplies.

Following this method, Kutusov turned north and west in limited pursuit of the Grande Armee. On November 3 Marshal Davout's I Corps were cut off from the main body of the French army at Viazma. French troops under Eugene, Poniatowski, and Ney turned back to free their comrades, but at a cost of 6,000 casualties, 2,500 prisoners and, more significantly, the total disarray of the once highly-disciplined I Corps.

Onset of Winter

In late October the first severe snows fell, accompanied by bitter frost and driving winds, covering the landscape and the sky in an unbroken whiteness. "Snow fell in enormous flakes; we lost sight of the sky and the men in front of us." Though swathed in fur and wadded coats, the men had no protection for their faces. Their lips became cracked, noses frost-bitten, eyes blinded by the glare. The horses in weakened condition could no longer haul the guns up icy slopes, and they began to be abandoned. As soon as anyone died, whether of wounds or frostbite, his fellows stripped him of his boots, any food in his haversack, and left him unburied to the wolves. "Pity was driven down to the bottom of our hearts by the cold, like mercury in a thermometer."

Tens of thousands fell in exhaustion and froze to death. Thousands more who wandered off in search of food and shelter were cut down by marauding Cossacks or murdered by an enraged peasantry.

Smolensk to Krasnoye

A tattered remnant of 75,000 made their way into Smolensk at the beginning of November. Napoleon had hoped to consolidate the Grand Army here for the winter. But there was to be no respite here, for news was received of two fresh Russian armies to the west, closing in on Napoleon's path of retreat. Wittgenstein from the north and Admiral Tchitchagov from the south were positioning themselves like the two jaws of a beartrap to crush Napoleon before he could get across the next major obstacle, the Berezina River.

On 9 November two Russian divisions captured Augereau's French brigade of two thousand men at Lyakhovo on the road between Elnia and Smolensk. Kutukov believed that this episode was peculiarly significant, for it was the first time in the war that an entire enemy unit had allowed itself to be taken prisoner.

On 12 November the first columns of the Grand Army trailed out of Smolensk. Disorder was growing in the ranks; lack of horses forced the abandonment of supply wagons and artillery.The corps were more than usually strung out, enabling Miloradovich to practically cut the army in two on the 15th, when he moved up from the south with his 16,000-strong command and placed himself across the main road over Krasnoye. Napoleon and the Imperial Guard, who had already passed through in safety, were able to doubleback and fight their way through the roadblock to free the trapped troops, but the encounter cost the Grand Army 6,000 dead and wounded and about 20,000 prisoners.

Crossing the Berezina

In the last week of November the surviving Russian and Napoleonic armies converged on the River Berezina. On the afternoon of the 25th, in the wake of a snowstorm, Napoleon arrived at the Berezina crossing at Borissov to find the weather had played a cruel trick. A week earlier the winter had seemed to be set in so firmly that he had burned his pontoon train at Orsha, confident that he'd be able to cross the frozen rivers dryshod. Now an unseasonable thaw had turned the ice into drifting mush, and the Grand Army was marooned on the east bank of the Berezina, looking across an icy torrent 300 yards wide, its bridge burned in three different places, irreparable in the face of heavy Russian fire from Tchitchagov's army on the far bank.

Napoleon had 49,000 men fit enough to fight and 250 guns. Wittgenstein with 30,000 men was sweeping in from the north, Tchitchagov with 34,000 men held he opposite bank, ready to contest any crossing, while Kutusov with 80,000 men was moving up from the rear.

Napoleon decided to make the crossing upstream near the village of Studienka north of Borissov, where the ford was only 100 yards across. Two bridges were constructed by 400 pontoneers up to their shoulders in the icy waters over a twenty-four hour span--a light one for the infantry, a heavier one downstream for wagons and cannon.

At one o'clock on 26 November 11,000 men began to cross the frail wooden life-line. By four o'clock the larger bridge was ready, and guns, wagons, and caissons rolled across. The crossing was still in progress two days later when Wittgenstein arrived close enough to bombard the bridges. Those remaining on the eastern bank now pressed forward in desperation to cross. Discipline broke down and troops, horses, and wagons in dense masses fought to get to the bridge entrances at the river. Adding to the disorder, one of the bridges collapsed under the weight of the guns, causing a rush to the other bridge which was jammed up even more.

Kutuzov's troops arrived on the scene to find the areas around the two enemy bridges "so obstructed with the bodies of men and horses that at some points it was possible to cross the Berezina on foot."

By the morning of November 29 Napoleon had succeeded in bringing all his fit troops across the bridges, at the cost of several thousand killed or wounded in the fighting, and another twenty thousand stragglers and refugees who were stranded and captured on the east bank.

End of an Army

I have no army any more! For many days I have been marching in the midst of a mob of disbanded, disorganized men, who wander all over the countryside in search of food.

--Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon left the banks of the Berezina with an army that was still sixty thousand strong but now wholly without organization--nothing in the shape of divisions, brigades, or regiments; cavalry, infantry, artillery all mixed up in a formless mass. Not just the campaign but the army Napoleon knew was lost beyond all hope of retrieval, and on 5 December he left the command in the hands of Murat and sped on by sledge to the Polish frontier, with the intent of reaching Paris to inform and reassure the people concerning the disastrous retreat.

The 'abandoned' army straggled on in an even more disordered and desperate fashion towards Vilna, losing many men every hour to the fury of the winter, the raiding Cossacks, and the slow-moving pursuit of the Russian army. The road to the Russian frontier now lay open, but it was a brutal path, instilling the most of both physical and moral distress.

On 14 December Marshal Ney led the troops over the frontier at Kovno, crossing the Niemen River that the Grand Army had poured across in three long impressive columns six months before. The campaign of 1812 was effectively at an end.

Wars of Liberation 1813-1814

A new struggle for liberation opened three years later with the defeat of Napoleon's grande armée in Russia. As the tsarist armies began to cross their western frontiers in December 1812, the crucial question became what reception they would find among the rulers and the inhabitants of central Europe. The first state to cut its ties to Paris was Prussia. It was not the king, however, but one of his generals, Ludwig Yorck von Wartenburg, who decided on his own initiative to cooperate with the Russians. Only hesitatingly and fearfully did Frederick William III then agree in February 1813 to a war against France, although public opinion in his kingdom greeted the outbreak of the conflict with enthusiasm. The other rulers of central Europe refused initially to follow the Prussian example.

The members of the Confederation of the Rhine were still convinced of Napoleon's invincibility, while Austria preferred to see the combatants exhaust each other to the point at which it could play the role of mediator and arbiter. The foreign minister in Vienna, Clemens Lothar von Metternich, was afraid that the hegemony of France in central Europe might be replaced by that of Russia.

He tried, therefore, to pursue a strategy of armed neutrality, hoping that he could persuade the opposing sides to accept a compromise by which an equilibrium would be maintained between Alexander I and Napoleon. This plan failed because of the obstinacy of the latter, who feared that concessions in foreign affairs would weaken his control over internal politics in France. The upshot was that in August 1813 Austria entered the conflict on the side of Russia and Prussia, and the balance of military power shifted in favour of the anti-French coalition. The faith of the secondary states in Napoleon's star began to weaken, and Bavaria became the first member to secede from the Confederation of the Rhine (October 8 ). One great allied victory would now suffice to bring all of Germany into the struggle against France.

That victory came on Oct. 16-19, 1813, at the Battle of Leipzig. After four days of bitter fighting, the French army was forced to retreat, and its domination of central Europe was finally at an end. Before the year was out, Napoleon had withdrawn across the Rhine. Of all his conquests in Germany, only the left bank was still under the effective control of Paris. The Confederation of the Rhine promptly collapsed, as its members rushed to go over to the winning side before it was too late.

The Rhineland was also reconquered early in 1814, after the allies had launched their invasion of France. In the course of the spring the capture of Paris, the restoration of the Bourbons, and the conclusion of peace in the first Treaty of Paris (May 30) ended the war of liberation except for the episode of the Hundred Days, when Napoleon briefly returned to power and was ultimately and finally beaten at Waterloo. The western frontier of central Europe was to remain essentially the same as at the time of the initial outbreak of hostilities more than 20 years before.

New state boundaries within Germany would still have to be determined, to be sure, and the problem of a new political organization of the nation awaited the victorious statesmen, but the period of foreign hegemony was over at last. The rulers of central Europe, relying partly on the forces of innovation, partly on those of tradition, had succeeded in freeing themselves from alien domination.

Now they had to decide what use they would make of their freedom. Would they create a new polity of unity and liberty, which many reformers demanded, or would they reestablish the old order of absolutism and particularism, which the conservatives advocated? As the statesmen began to gather in Vienna in the fall of 1814 to restore peace to a continent ravaged by two decades of war, they pondered the problem of devising an enduring form of government for Germany.

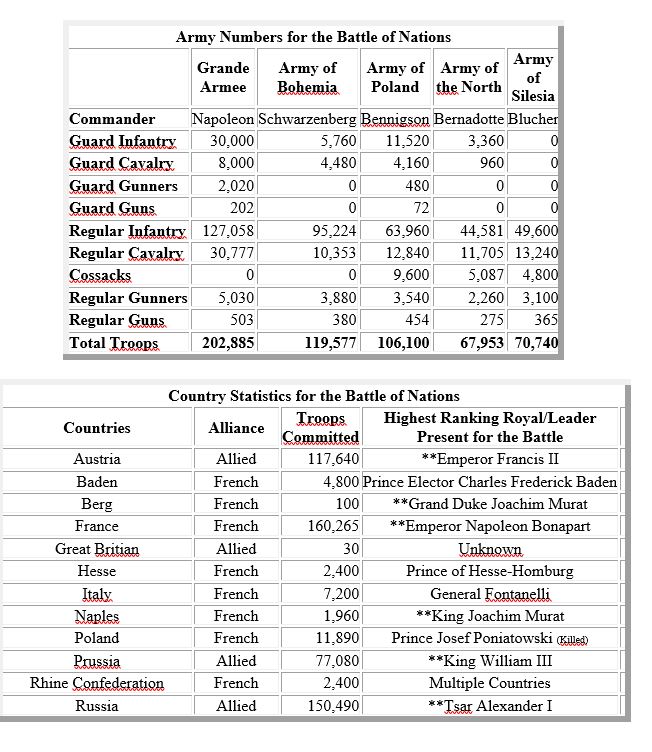

The Battle of Nations (Battle of Leipzig)

Never had there been a greater clash of arms, nor would there be till the 1st World War. Leipzig will stand in history as one of the greatest battles of all time, forever, breaking the grip of Napoleon in central Europe. After the disastrous 1812 Russian campaign, over half a million men in five armies would settle the fate of Germany as well as the fate of Europe itself. This battle would begin October 14, and last through October 19, 1813.

Napoleon’s attempt to fight and destroy each army in detail had failed. He had been forced to give up Dresden and was falling back on his communication lines, back toward France. There he could fight all the armies on his own terms. The communication line lead through Leipzig. The only problem with falling back meant leaving Germany, which would allow his German allies to leave his side. His only chance to pull any of this off was not to commit to a battle until he crossed the river at Leipzig. As the Allied Armies got closer, smaller but escalating battles began to occurred. This included Liebertwolkwitz, which was the greatest cavalry battle in history, and forced Napoleon to fight.

The Coalition Allies’ intention was to mass every available man against the main French Army. Napoleon’s intention was to smash the Army of Bohemia before such a concentration of strength could occur. The result was the largest land battle of the Napoleonic Wars.

October 16, opened with the Army of Bohemia attacking the French before Napoleon was ready to start his attack. To the Southwest, the attacking Austrians, caught in a maze of bad terrain, failed to gain much ground, with Meerveldt being captured and Gyulai being trashed be Bertrand. To the South, where both sides made their main effort, all Coalition reserve formations kept moving forward and finally halted and eventually drove back the French attackers. The fighting to the Southeast went similarly to the flow of fighting to the South. To the North, the unexpected arrival of Blucher’s Army of Silesia tied down French reserves. These badly needed reserves were intended for the French main effort, including a terrific combat between Marmont’s French VI Corps and York’s Prussian I Corps around Mockern that cost each corps over 8,000 casualties.

October 17, saw little action. Reinforcements for both sides arrived, tipping the numerical advantage even further in the Coalition’s favor. Seeing the need to withdraw, Napoleon ordered his forces to fall back into a tighter perimeter to cover Leipzig-Lindeneau line of retreat during the night of October 17/18.

October 18, saw the Coalition Allies, sure of the arrival of their late Army of the North, open with an offensive all along the line. The French repulsed all attacks from the south, and Bertrand again attacked and defeated Gyulai to clear the retreat route to the southwest. Blucher gained ground in the North, but was stopped short of blocking the French retreat route. Ominously for Napoleon, during the fighting a number of Saxon and Wurttemberger units defected to the Coalition.

By the night of October 18/19, the French retreat was well underway with most of the army’s trains and cavalry and a number of infantry corps already across the Lindeneau bridge and marching to safety. The French at this point were pulling off a well executed fighting withdrawal. On the morning of October 19, Colonel Montfort’s left a corporal and four sappers at the Elster Bridge with orders to await his return. The Colonel was attempting to get precise plans on how the rearguard was to cross before the bridge was to be blown. The corporal, having watched many troops, the Emperor and his suite, and an immense convoy of artillery and baggage go past, could see only a long procession of stragglers and wounded. Then he saw those men charged and cut down by Prussian cavalry.

Since Colonel Montfort was very late getting backing and convinced that this was the Coalition advanceguard and that the French Army had already crossed, he blow the bridge. This fatal error trapped a whole army corps and part of another, defending Leipzig and allowing the army to escape. The enemy horsemen where only a few foragers and where cut down by the leading troops of the rearguard. In Leipzig thousands of stragglers and wounded were also still in the city. This turned a serious check into a disaster. The other great loose to Napoleon was Prince Josef Poniatowski, who had become the only foreign French Marshal just days before.

Many resources have placed French loses at anything from 20,000 to 100,000 men. However, if you consider the loose of two corps because of the bridge, the numbers do rise. I would put estimates at around 90,000 men. Resources have placed Coalition loses at between 50,000 and 60,000 men. I would place there loses around 60,000 due to the aggressiveness of the Coalition.

Original Source:

http://www.fortunecity.com/victorian/riley/787/Napoleon/

Does NOT exist anymore!