Paris

Paris (Ancient Greek: Πάρις), also known as Alexander (Ancient Greek: Ἀλέξανδρος), the son of King Priam and Queen Hecuba of Troy, appears in a number of Greek legends.

Of these appearances, probably the best known was the elopement with Helen, queen of Sparta, this being one of the immediate causes of the Trojan War. Later in the war, he fatally wounds Achilles in the heel with an arrow as foretold by Achilles's mother, Thetis.

The man and the circumstances

Some have thought that just as Hector could be the incarnation of bravery, his brother Paris could be that of cowardice. For that reason, reproaches of all kinds have fallen upon the head of this handsome man, whose deeds, some affirm, caused the ruin of Troy.

Yet, the burden of cowardice may be heavier than the toil of courage, and it also takes a man to bear it to the end of time. Courage has its reward, but for him who has been appointed by nature or the gods to play the part of the coward, there is no rest, now or later.

And these issues being matter of opinion, Paris was also accused, near the end of his life, of being too bold.

Courage comes and leaves as it pleases. For even Hector, the bravest among the braves, trembled when he confronted Achilles, and ran away, being pursued by his enemy around the walls of Troy like a hare by a dog. And if he finally faced Achilles, it was because a goddess, who wished his death, fooled him to do so.

And what brave Hector, though being the pillar of Troy, could not accomplish in close combat, was later done by Paris from the distance. For he, using weapons adapted to what has been thought to be his less audacious nature, put an end to Achilles' life, thus avenging the brother who had despised him.

But all these matters were, as it is said, on the knees of the gods. Being so, a seducer was needed, since it was the will of Zeus to make his daughter Helen famous for having entangled Europe and Asia in hostility. Others assert that the god just wished to exalt the race of the demigods.

In any case, Zeus, having planned with Themis how to bring about the Trojan War, appointed the shepherd Paris to judge the goddesses in Mount Ida, where Aphrodite gave him the promised bribe—Helen—in exchange for the Apple of Eris (Discord) that Paris awarded her.

Life and deeds of Paris

Birth

Paris was the second child of Queen Hecabe of Troy. Just before his birth, Hecabe dreamt she had brought forth a firebrand that destroyed the city of Troy. When this dream was known, the diviner Aesacus, who had learned to understand the meanings of dreams because he had been taking lessons in this art from the seer Merops, the father of King Priam's first wife Arisbe, advised to expose the child, prophesying that Paris was to become the ruin of the city.

But that is not the way Paris himself understood the dream at the time when he went to fetch Helen. For he believed that the fire referred to the torch of his heart burning of love for Helen.

Upbringing

So, when Paris was born, King Priam, following Aesacus's interpretation of the dream, gave his and Hecabe's son to a servant Agelaus, with instructions to expose him on Mount Ida, near Troy. Agelaus did as he was told, but when he returned after five days, seeing that the child had survived because a bear had nursed him in the wilderness, carried him away, and bringing him up as his own son, he named him Paris.

This boy grew up to be a very handsome and strong young shepherd who also defended the flocks from robbers, and it is at this time that he was surnamed Alexander.

His first love

Once, while he was tending his cattle on Mount Ida, the young shepherd fell in love with the nymph Oenone, daughter of the river god Cebren. This girl was possessed by a divinity, and some say that it was Rhea who taught her the art of prophecy, but herself she says that it was Apollo. In any case, as the rumour went, she was able to foretell the future, and also obtained renown for being a woman of wisdom and understanding.

Paris took Oenone to Mount Ida, where he had his home, and being very much in love with her, promised her continuously, as lovers often do, that he would never desert her. But almost everybody knew Paris' deeds before Paris himself, and so Oenone, though acknowledging that he for the moment was profoundly in love with her, said that she knew that one day he would fall in love with an European woman, whom he would bring back with him, carrying with her all the horrors of war.

And to this disappointing picture, she added that he was to be wounded in that war, and that nobody would be able to cure his wound except herself, who was well acquainted with the Phrygian forests and its healing herbs. This nymph, who loved Paris when he still was a poor shepherd (for at the time it was not known that he was a Trojan prince) never accepted, though she foretold it, that this young man, who had gone around writing "Oenone" with his blade in the trunks of the trees, could endure to desert her. Also the seeress Cassandra told her that her love was a fruitless one, for when she knew what Oenone was up to, she said:

"What are you doing, Oenone? Why commit seeds to sand?" (Cassandra to Oenone. Ovid, Heroides 8.115).

Destiny comes from far away

At this time the gods attended the wedding party of Peleus and Thetis, to which Eris (Discord) was not invited. And being in pain because of anger and jealousy, this persistent goddess decided to spoil the feast, and though unwelcome, she appeared and threw among the guests one of the Apples of the Hesperides, in which the inscription "for the fairest" could be read.

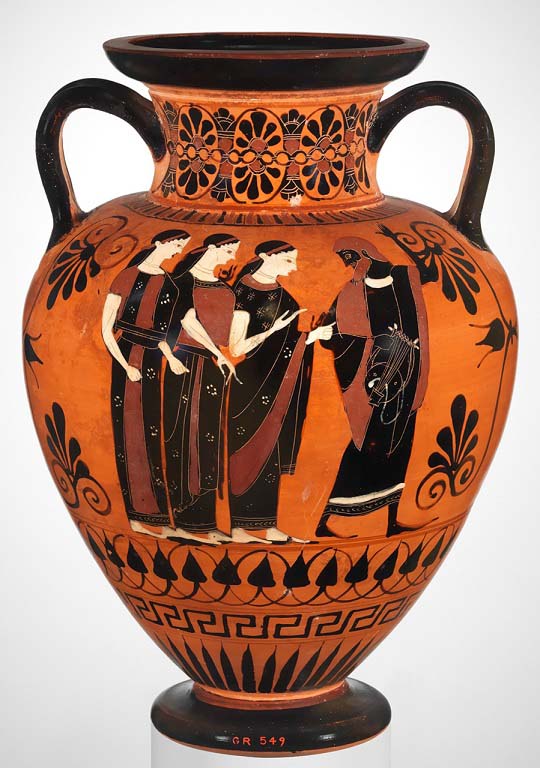

Helping herself through that device, she succeeded in starting a dispute between Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite. So Zeus, who knew the otherwise anonymous shepherd Paris, appointed Hermes to lead the three goddesses to Mount Ida in order to be judged by the same shepherd, and in that way put an end to the quarrel.

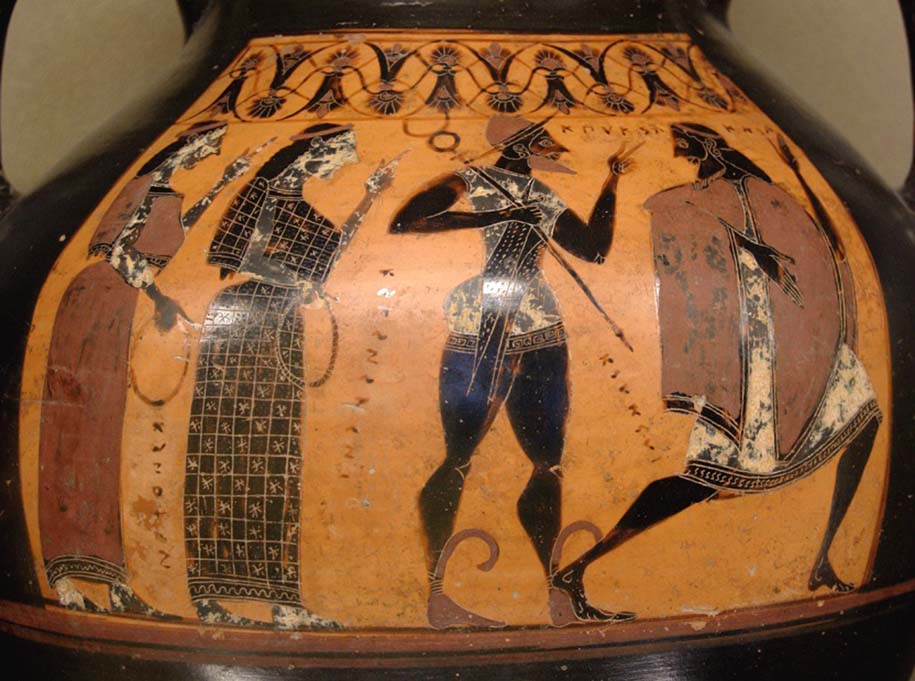

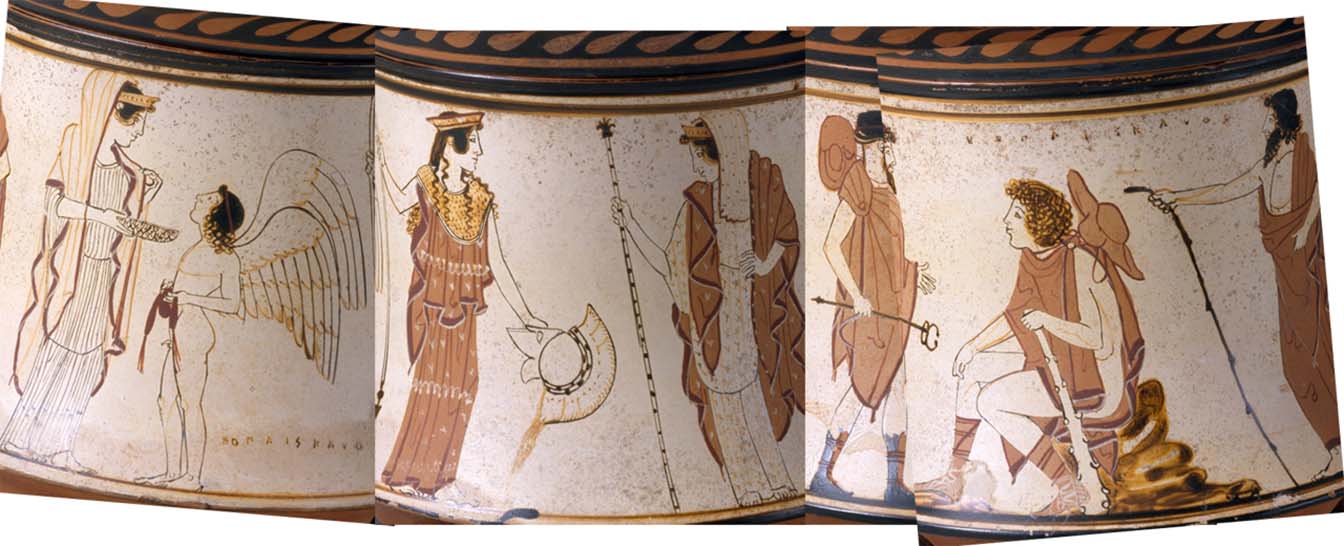

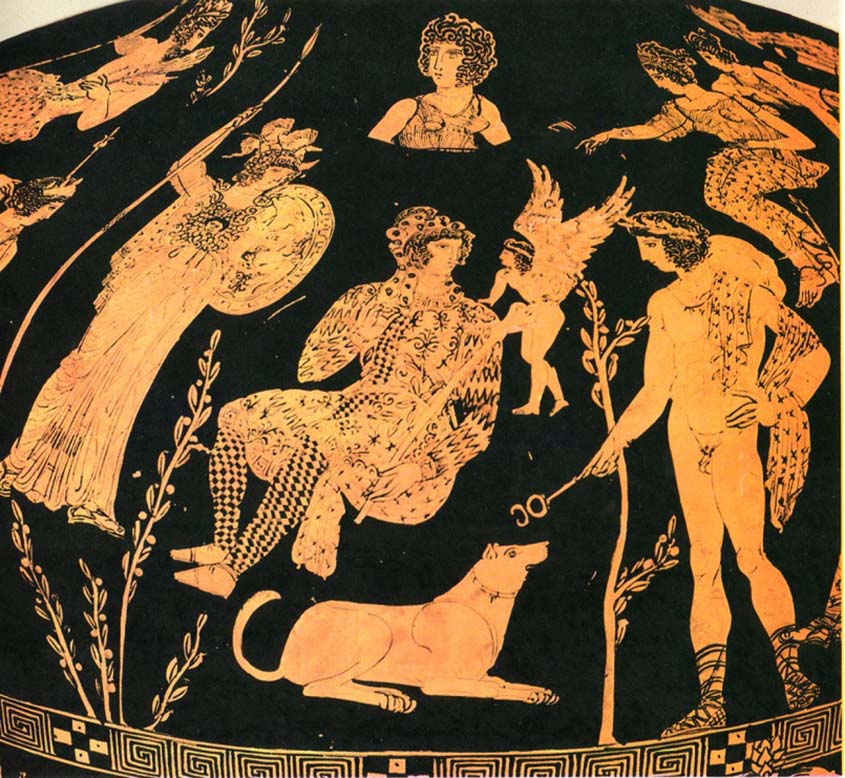

The Judgement of Paris

When Hermes came to Mount Ida with the three goddesses, he called Paris and said to him:

"Come here and decide which is the more excellent beauty of face, and to the fairer give this apple's lovely fruit." (Hermes to Paris. Colluthus, The Rape of Helen 130).

While Paris reflected, the goddesses, who for the occasion had bathed their immortal bodies, offered him bribes in order to win Eris' award of beauty: Athena offered him the command of Phrygia and the destruction of Hellas, or as some say, that he would be bravest of mortals and skilled in every craft. Likewise Hera offered him, besides wealth, the dominion over Asia and Europe.

But Aphrodite offered him the hand of Helen, whose beauty was famous worldwide, and this bribe won the Apple.

What Paris did not think about

From the moment he thought he could get the daughter of Zeus, there was no more "Oenone" for Paris, and he thought the bribe to be most splendid. The fact that Helen was already a married woman, herself mother of a little daughter, did not disturb his heart, nor the fact that he was second, not only in marrying her, but also in stealing her.

For Theseus had already abducted her years ago, and she was not a maid when the DIOSCURI rescued her, razing the city of Aphidnae where Theseus kept her hidden. So what happened to Troy had already been rehearsed in Attica for the sake of the same woman, who, as some suggest, was perhaps inclined to lend herself to theft.

Even less did Paris evaluate his new bride's real dowry: a powerful fleet of avenging war-ships, determined to ruin Paris' city and family, and to bring the stolen beauty back. And above all he earned the eternal enmity of the two spurned goddesses, who never forgave him, nor his family nor his whole country, the humiliation they had suffered.

What he did think

Paris regarded his own judgement quite fit. For love, he reasoned, was greater than power or a brave heart, and to follow the path traced by Theseus was rather something to be proud of, for Theseus was a great man, except in that he lost Helen, a mistake that Paris intended to correct on his own account.

In fact he considered the whole scene and his acquaintance with the goddesses as a favor and a sign of his growing fortune. And as if fate had decided to make him prosper, he saw one favor being followed by another, for his royal origin having been discovered, he changed the life of the shepherd for that of the prince.

Another coup of fortune

This is what happened: Some servants of King Priam came to Mount Ida in order to fetch a bull to be given as prize in funeral games. Paris followed them because this was his favorite bull, and having decided to participate in the games, he defeated all other contenders, including his own brothers.

One of them, Deiphobus was so angry on account of his defeat that he drew a sword against him and would have killed him, had not Paris quickly taken refuge at the altar of Zeus. It was then that the seeress Cassandra declared that Paris was her brother, and Priam then acknowledged him as his son, receiving him into his palace. This is how Paris, who had been expelled from the city following the advice of one seer, was taken back in accordance with the advice of another seer.

Shepherd becomes prince, and now he can travel

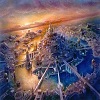

When by such wonders the shepherd saw himself turned into a prince, it came the time for Paris to go and fetch the prize he had preferred when he happened to act as a judge. Back in Mount Ida, Phereclus, son of Tecton, son of Harmon, built the ships that Paris needed in order to sail to Lacedaemon and reach Sparta, where Queen Helen lived.

More warnings

Some say that Oenone still was around begging him not to sail, and warning him of the consequences of the actions he was about to perform. It is also said that his sister Cassandra uttered new fiery prophecies as Paris sailed:

"Where are you going? You will bring conflagration back with you. How great the flames are that you are seeking over these waters, you do not know." (Cassandra to Paris. Ovid, Heroides 16,120).

But as before, Paris thought that those flames just described the love he felt was burning in his heart. So he left, trusting that Aphrodite, whom he had painted on his sail, would favor a gentle breeze and a calm sea; for having rose from the waves, it was natural to think that she could tame them, which apparently she did, by putting him on the way that was also to calm his heart.

Paris in Sparta

When Paris landed in Lacedaemon, he was first received by the Dioscuri, brothers of Helen, but soon he went to Sparta, where he became King Menelaus' guest, and in the course of a party he gave gifts to Helen. Menelaus entertained him for nine days, but then he had to leave for Crete in order to attend the funeral of his grandfather Catreus, who had been accidentally killed in Rhodes by his own son Althaemenes, having been taken for a pirate or an invader when he disembarked by night. Thus an oracle was fulfilled, for it had been predicted that Catreus, son of Minos, would die by the hand of one of his children, and the one child who exiled himself to avoid the oracle was the same who brought it to completion.

On leaving, said Menelaus:

"Look to my affairs, and to the household, and to our guest from Troy." (Menelaus to Helen. Ovid, Heroides 17.160).

Menelaus then set sail for Crete, after having ordered Helen to furnish the guests with all they required, which she did in all details, for as some say, from the moment she met Paris—the young prince who had renounced the riches of the world for her sake—she gazed at his dashing presence with no little admiration, possessed as he was by Aphrodite, who was now his only pilot and sponsor. And not less persuading was his talk about the golden houses, magnificent temples, and lofty towers of Troy, riches not to be found in niggard Sparta. As soon as Menelaus sailed to Crete, also the companionless beds started haunting them.

For nothing seems more wasteful to those pierced by love and desire than to go and lie alone in separate bedrooms while being under the same roof.

No consequences

To Paris' mind there was no risk in the escape: the master of the house was away, and on the shore the Trojan fleet, well equipped with arms and men, was ready. As for the consequences of the abduction, there was, according to Paris, nothing to fear, for never before had a war broke out for a stolen woman. Boreas ravished Orithyia, daughter of King Erechtheus of Athens, and took her to Thrace, and there was never an Athenian invasion of that country. Jason the Argonaut took with him, besides the Golden Fleece, the king's daughter Medea, and though they were persecuted by the Colchian fleet, the invasion of Thessaly never took place.

Theseus abducted Ariadne, the daughter of King Minos of Crete, and yet Minos did not call to arms. And some say that Io was also taken to Egypt by force, and Europa was removed from Phoenicia, and yet none of these events led to war. It seemed then to Paris that even if most people think it unjust to carry women off, the will to avenge rape is weak, for apparently many believe that the women would never have been abducted, had they not wished it themselves. And so he deemed the risks for retaliation as almost non-existent.

Helen's apprehensions

On her side, Helen always felt that she still had a reputation to take care of. For Theseus, she says, did not lure her away but seized her by force, and yet he did her no harm when she was a captive, but just stole a few kisses, so that when she was returned to Sparta by the DIOSCURI, she was untouched. To become an adulteress living in a foreign land was not an easy step to take, since being abroad without the support of family and friends could be difficult if she ever met harm.

For Jason promised many things to Medea, but then he got tired of her and looked for a younger princess, leaving Medea alone and defenceless, and forcing her to go from land to land, and in each cope with the difficulties of exile, until one day she returned to Colchis.

Farewell Sparta

But Aphrodite had promised to bring Helen and Paris together; so while Menelaus was still in Crete, they put many treasures on board, and sailed away by night, leaving Helen's and Menelaus' daughter Hermione behind, who was then nine years old. As the Trojan fleet still was in the Laconian Gulf, Helen and Paris consummated their marriage in the island of Cranae. Now Hera started to go against the couple, and because of her they met heavy storms at sea, which obliged them to put in at Sidon, a coastal city of Phoenicia, which some say was in reality taken by force by Paris and his troop.

In Sidon, Paris purchased or stole richly broidered robes which he gave to his mother when he reached Troy. In the meanwhile, Helen's brothers, the Dioscuri, disappeared from this world after Idas and Lynceus killed Castor when the latter and Polydeuces were stealing their cattle. Some say that Paris and Helen, fearing persecution, spent much time in Phoenicia and Cyprus, but others affirm that they reached Troy in three days, having a fair wind and a smooth sea. It is told that when the seeress Cassandra saw Helen coming into Troy she tore her hair and flung away her golden veil, but the city nevertheless received this woman as a jewel which would enhance its beauty.

Menelaus informed

When Menelaus learned, through Iris, what had happened, he, along with his brother King Agamemnon of Mycenae, started planning an expedition against Troy. For this purpose they gathered many other rulers from the whole of Hellas, and a powerful fleet met at Aulis, a Boeotian city opposite the island of Euboea, in order to sail to Troy, and get Helen and the stolen property back, either by persuasion or by force.

The seducer considered guilty by his own brother

That is how what was deemed unlikely to happen (since it had never happened before), that is, war for the sake of a woman, was now unavoidable unless Helen and the property were restored. There were Trojans who wished to do so, but they apparently were a minority, and neither King Priam nor the crown prince Hector ever compelled Paris to give back lovely Helen, in spite of the accusations which fell upon the head of the seducer:

"It is your fault that this city is invaded by the sounds of battle." (Hector to Paris. Homer, Iliad 6.327).

The gifts of the gods cannot be refused

During the last year of the war there was an attempt to solve the conflict by a single combat to be fought between Paris and Menelaus. Paris was at first reluctant to fight and Hector reproached him:

"Are you too cowardly to stand up to the brave man whom you wronged? You would soon find out the kind of fighter he is whose lovely wife you stole. Your lyre would not help you at all, nor Aphrodite's gifts … But the Trojans are too soft. Otherwise you would have been stoned to death long ago for the evil you have done." (Hector to Paris. Homer, Iliad 3.45).

Paris, who would not compete with his brother's courage, praised brave Hector, and accepted both the reprimand and the duel with Menelaus, but he also said:

"There is something you must not reproach me for: the lovely gifts I have from Aphrodite. The precious gifts that the gods lavish on a man unasked are not to be despised, even though he might not choose them if he had the chance." (Paris to Hector. Homer, Iliad 3.65).

Duel with Menelaus

This is how Paris fought with Menelaus, and got almost killed. But when Menelaus, during the fight, seized him by the horsehair crest of the helmet and began to drag him, Aphrodite came and broke the strap of the helmet, so that it came away empty in Menelaus' hand, and then, to escape Menelaus' renewed attack, the goddess hid Paris in a mist, and took him to his own bedroom in the city, where he soon met Helen in a kind of duel that suited him better:

"Come, let us go to bed together and be happy in our love." (Paris to Helen. Homer, Iliad 3.440).

Paris' style

That was, generally speaking, the kind of engagement which interested Paris, far more, no doubt, than the war which, as they say, he had himself caused. So while Hector and others were seen making superhuman efforts in the battlefield, Paris could occupy himself at length attending his armour, shield, and bow in the palace, with Helen sitting beside him. That is why Hector reproached him:

"It is because of you that the battle-cry and the war are ablaze about this city. You would be the first to quarrel with anyone else whom you found shirking his duty in the field." (Hector to Paris. Homer, Iliad 6.330).

And yet Hector did not think of Paris as being a coward altogether:

"You have plenty of courage. But you are too ready to give up when it suits you, and refuse to fight." (Hector to Paris. Homer, Iliad 6.520).

Those killed by Paris

Paris, who is frequently seen aiming his arrows at several Achaean warriors including Diomedes whom he wounded, killed many men in battle (see below).

Killed by Paris:

Achilles, Cleodorus (a Rhodian), Cleolaus (the henchman of Meges, commander of the Epeans), Deiochus, Demoleon (a Laconian in Menelaus' army), Eetion, Euchenor (son of the seer Polyidus - his father told him that he must either die in bed of a painful disease or sail with the Achaeans and be killed at Troy), Evenor (a man from Dulichium, which is one of the Echinadian Islands at the entrance of the Gulf of Corinth), Menesthius (a Boeotian), Mosynus and Phorcys (both from Salamis. They came in the ships of Ajax).

Polydamas reproaches him his courage

After the death of Hector, Polydamas, the same man who so many times had given Hector tactical counsel in battle, recommended now to give back Helen and her wealth, lest the city be destroyed. But the Trojans assembled, though approving his proposal, did not dare to defy the sweet prince Paris. So he, talking in council, called Polydamas a coward more than once, and it was then that Paris was accused of being too brave:

"You most mischievous man, your courage brings us misery … That strife should have no limit, save in utter ruin of fatherland and people, for your sake. Never may such valour craze my soul." (Polydamas to Paris. Quintus Smyrnaeus, The Fall of Troy 2.85).

Paris' moment of glory

It was fated that Achilles would die short after the death of Hector, and he who fulfilled that prophecy was the archer Paris, who shot him in the ankle. However, some say that it was Apollo who did this, and still others say that both Apollo and Paris killed him. But no man could kill another had not a god allowed it.

Another way of killing Achilles

There are also those who say that Achilles died in a different way: He fell in love with King Priam's daughter Polyxena, they say, and wishing to marry her, he came for an interview with her brothers Paris and Deiphobus, and they treacherously murdered him when they met.

It is on account of this, they assert, that Polyxena was, after the sack of Troy, slaughtered on the grave of Achilles by the Achaeans. In any case, Paris is said to have fought for the body of Achilles, being this his greatest day in war. It could be thought at the moment that there could be salvation for Troy, and it was him, the weak seducer, who had avenged his brave brother Hector's death.

As old prophecies are used up, new ones are uttered

At this crucial moment, in the tenth year of the war, as old prophecies were used up, new prophecies were uttered by the Achaean SEERS, regarding the way in which Troy could be taken, and Calchas declared that the Bow & Arrows of Heracles should be fighting on the Achaean side if Troy was to be taken.

Philoctetes fetched

That is why an embassy was sent to Lemnos to bring Philoctetes and the bow back to the front. Philoctetes, in his way to the Trojan War, had been bitten by a water-snake in Tenedos, and as the wound did not heal the army put him ashore on the island of Lemnos, where he, by shooting birds, survived in the wilderness, or perhaps being attended by Iphimachus, a Lemnian shepherd.

Paris badly wounded

Philoctetes was either persuaded or forced to come with his bow. On his arrival he was healed by Podalirius, one of the sons of Asclepius, and going into battle he shot a poisoned arrow at Paris and injured him.

First love revisited (I)

The wounded prince returned to the city and spent a night in pain, for there were no remedies at Troy able to put this damage aright. So now was the time to remember Oenone's prophecies, and her talk about the miraculous healing herbs from the Phrygian forests, which the nymph knew so well and had promised to apply to whatever wound he got in war. So as his life fainted, he came back to his first love, but as a suppliant, and was received with no little amazement.

He called Oenone "wife"; he blamed fate for having dragged him to Helen, and asked Oenone to be merciful and banish his pain. But Oenone was too bitter to do anything like that. Instead he told him to go now to Helen and be healed by her and be blissful in her arms, and then she cursed him in various ways, as he left stumbling through the brakes of Mount Ida, which he never left, for he died there.

Oenone deplored her own wickedness and later, having found the body of the husband she had not ceased to love, she burned it and leapt onto his funeral pyre, and was herself burned to death.

First love revisited (II)

However, others say that Paris did not go to Ida, but that he instead sent a messenger to Oenone, asking her to hasten to Troy and heal him, saying also that she should forgive him, for all events happened, he argued, through the will of the gods. Her answer has been reported to be the same, that is, that he had better go to Helen, and ask her for healing. But it is told that, all the same, she left as fast as she could for Troy, willing to heal him.

However, the messenger arrived first and delivered her bitter reply, and on hearing it, Paris gave up all hope and died. When she arrived, Paris, for being dead, could no longer forgive her refusal, and Oenone, unable to forgive herself, committed suicide. Such were the things that happened to Paris and Helen, but others have said otherwise, and still others affirm they did not happen at all.

Sources

Homer, Iliad

Epic Cycle, The Cypria Fragments - Greek Epic C7th - 6th B.C.

Apollodorus, The Library - Greek Mythography C2nd A.D.

Strabo, Geography - Greek Geography C1st B.C. - C1st A.D.

Pausanias, Description of Greece - Greek Travelogue C2nd A.D.

Ptolemy Hephaestion, New History - Greek Mythography C1st - 2nd A.D.

Colluthus, The Rape of Helen - Greek Epic C5th - 6th A.D.

Hyginus, Fabulae - Latin Mythography C2nd A.D.

Ovid, Heroides - Latin Poetry C1st B.C. - C1st A.D.

Statius, Achilleid - Latin Epic C1st A.D.

Apuleius, The Golden Ass - Latin Novel C2nd A.D.

Photius, Myriobiblon - Byzantine Greek Scholar C9th A.D.

"Greek Mythology Link"