Pelops

In Greek mythology, Pelops (Ancient Greek: Πέλοψ) was king of Pisa in the Peloponnesus region (Πελοπόννησος, lit. "Pelops' Island").

His father, Tantalus, was the founder of the House of Atreus through Pelops's son of that name.

He was venerated at Olympia, where his cult developed into the founding myth of the Olympic Games, the most important expression of unity, not only for the people of Peloponnesus, but for all Hellenes.

At the sanctuary at Olympia, chthonic night-time libations were offered each time to "dark-faced" Pelops in his sacrificial pit (bothros) before they were offered in the following daylight to the sky-god Zeus (Burkert 1983:96).

The House of Atreus

Pelops though is not famous for his kingly characteristics, but is known for being a member of the House of Atreus, the most cursed family in Greek mythology.

The curse placed upon the House of Atreus started before the time of Atreus himself, and was first brought down upon the family line by Tantalus.

Tantalus was the son of Zeus, and would become the king of Sipylus, and by the nymph Dione, Tantalus would become father to Niobe, Broteas and Pelops.

The Banquet of Tantalus

Tantalus was in a privileged position, and was privy to some of his father’s plan, this though made him conceited, and taken to exceeding the boundaries expected of mortals. On one occasion Tantalus even went as far as playing a “joke” upon the gods.

Tantalus invited all of the gods of Mount Olympus to a fantastic banquet, and for some unknown reason, Tantalus decided that the main course would be made from the body parts of his own son Pelops. Thus Pelops was killed and cut up before being served to the gods.

All bar Demeter, amongst the gods saw what Tantalus had done, and refused to eat, but Demeter was distracted, for her daughter Persephone had gone missing, and automatically took a bite from the meal in front of her.

The gods would bring Pelops back to life, but one bone was missing, the shoulder having been consumed by Demeter, and so the goddess crafted a replacement bone from ivory.

When Pelops was brought back to life he was an improved version of himself, for the work of the gods had made him more handsome than before.

The actions of Tantalus was said to be the starting point for the curse placed upon the House of Atreus; and whilst ultimately Tantalus would be punished in Tartarus for eternity, his children would suffer also for Niobe would witness the slaughter of her children, and Broteas self-immolated.

Pelops comes to Pisa

Pelops himself would leave Sipylus, and arrive at the kingdom of Oenomaus at Pisa (Greece). Some tales tell of his voluntary departure, whilst others tell of how he was forced out by the military endeavours of Ilus.

Oenomaus was a king favoured by the god Ares, and the Olympian god has present Oenomaus with both weapons and horses. Oenomaus also had a beautiful daughter, Hippodameia.

Pelops brought with him a great wealth, but this was not enough to convince Oenomaus to allow Pelops to marry Hippodameia, for an Oracle had told the king that any future son-in-law would kill Oenomaus.

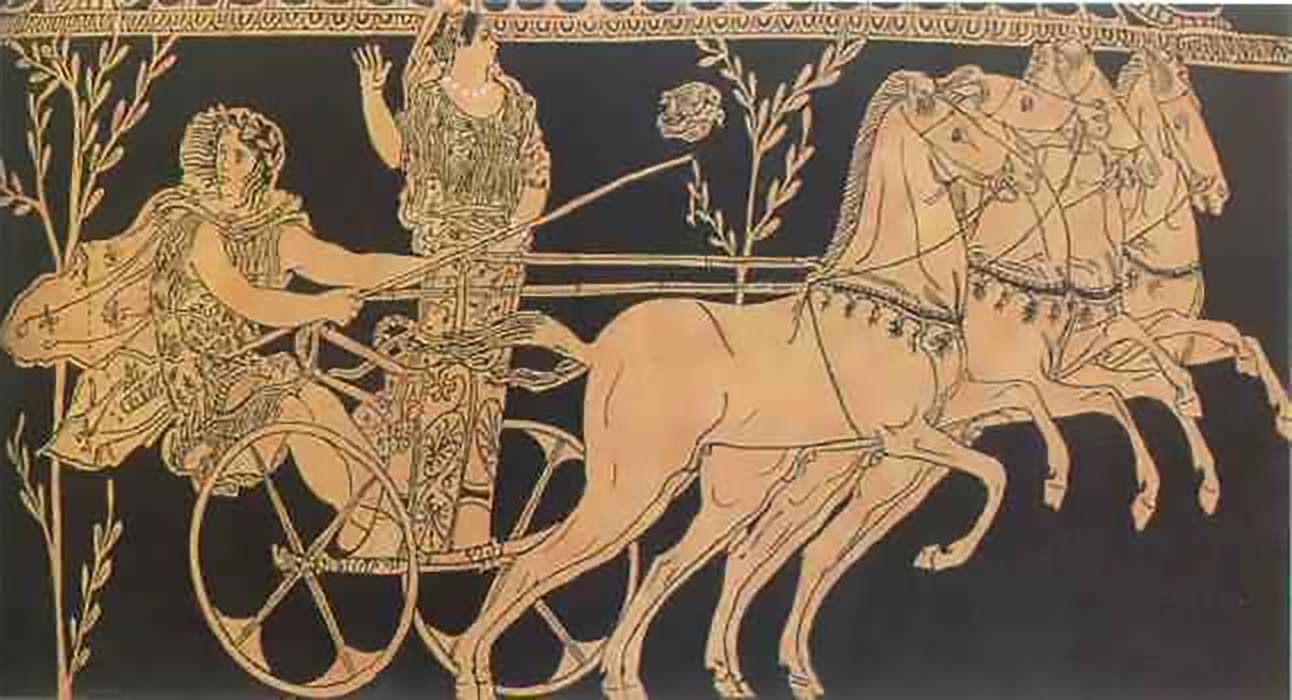

Oenomaus had devised a plan which would hopefully dissuade all potential suitors of Hippodameia, for the king proclaimed that only the first person to outrun his own chariot in a race to the Isthmus of Corinth would win his daughter’s hand. If though the suitor did not outrun his chariot then they would be killed, and their head placed upon a spike in front of the palace.

A race against a chariot pulled by horses of Ares and potential death was not enough to dissuade all suitors though, and even before Pelops arrived 19 men had attempted the race, and of course 19 men had failed.

Becoming King

Initially confident, Pelops became concerned when he saw the heads of those who had gone before upon their spikes.

Deciding that he could not win by fair means, Pelops decided to cheat, and convinced Myrtilus, the king’s charioteer to assist him. Pelops was said to have promised Myrtilus half of the kingdom of Pisa, if he would help Pelops win the race.

Some say it was not Pelops who did the conspiring but was Hippodameia herself, with the daughter of Oenomaus having fallen in love with the handsome Pelops.

Myrtilus, when he set up Oenomaus’ chariot, did not put the lynchpins in place, and as Oenomaus raced the chariot of Pelops, so the chariot effectively fell to pieces, and Oenomaus was dragged to his death. Realising what Myrtilus had done, Oenomaus, with his dying breath, cursed his servant, proclaiming that Myrtilus would die at the hand of Pelops.

Now Pelops himself found himself in a great position, for he could now wed Hippodameia, and with Oenomaus dead, he would have a kingdom to rule over. Pelops though soon realised that if he immediately gave Myrtilus half the kingdom, it would be obvious that King Oenomaus had not died by accident. To hide his part in regicide, Pelops instead decided to do away with his co-conspirator, and so Pelops through Myrtilus into the sea, the point where Myrtilus fell would become known as the Myrtoan Sea.

Even as he fell though, Myrtilus himself had time to place a curse on his murderer, condemning the family line of Pelops to generations of strife.

Olympic games

After his victory, Pelops organized chariot races as thanksgiving to the gods and as funeral games in honor of King Oinomaos, in order to be purified of his death. It was from this funeral race held at Olympia that the beginnings of the Games were inspired. Pelops became a great king, a local hero, and gave his name to the Peloponnese.

Walter Burkert notes that though the story of Hippodamia's abduction figures in the Hesiodic Catalogue of Women and on the chest of Cypselus (c. 570 BCE) that was conserved at Olympia, and though preparations for the chariot-race figured in the east pediment of the great temple of Zeus at Olympia, the myth of the chariot race only became important at Olympia with the introduction of chariot racing in the twenty-fifth Olympiad (680 BCE). G. Devereux connected the abduction of Hippodamia with animal husbandry taboos of Elis, and the influence of Elis at Olympia that grew in the seventh century.

Pelops' Family

The curse itself had no immediate impact upon Pelops, for the new king of Pisa sought, and received, absolution for his crimes from the god Hephaestus. He also built a magnificent temple dedicated to Hermes, this Pelops did to avert the anger of the god, for Myrtilus was a mortal son of the messenger god.

Pisa would flourish under Pelops, and the king would expand to take in new territory, including Olympia and Apia. This expanded area would be named Peloponnesus by Pelops.

The prosperity of Pelops and his kingdom was helped in no small part because of the king’s planning. Firstly, Pelops married off his sister Niobe to King Amphion of Thebes, and so gained a powerful ally.

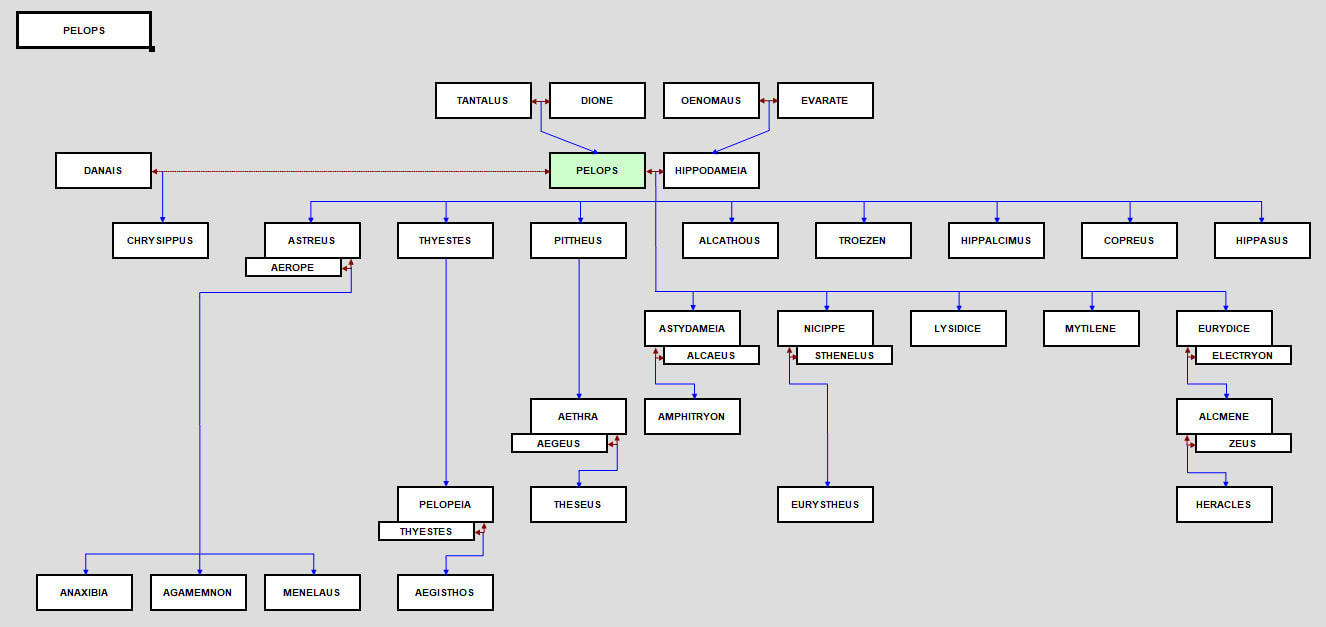

Pelops then did likewise with many of his children, and Pelops had many children.

Alcathous – Alcathous married the daughter of King Magareus of Onchestus, and would succeed his father-in-law to the throne.

Astydamia – Astydamia married a son of Perseus, Alcaues, the king of Tiryns, and became mother to Amphitryon,

Atreus – Atreus would become king of Mycenae, and father of Agamemnon and Menelaus.

Copreus- Copreus was exiled from Elis, but would gain favour in the court of his own nephew, King Eurystheus of Mycenae, where the son of Pelops would be the king’s herald.

Eurydice – Eurydice would marry King Electryon a king of Tiryns and Mycenae, and via Alcmene would come grandmother of Heracles.

Hippalcimus – Hippalcimus would become known as a named Greek hero, when the son of Pelops sailed on board to Argo with Jason and the other Argonauts.

Hippasus – Hippasus was possibly the King of Pellene.

Lysidice – Lysidice would marry Mestor.

Mytilene – Mytilene would become a lover of Poseidon.

Nicippe – Nicippe would marry the Mycenaean king Sthenelus, and give birth to the future king Eurystheus.

Pittheus – Pittheus would become the king of Anthea, and then a new city, Troezen, and via Aethra, would become grandfather to Theseus.

Thyestes – Thyestes would become the king of Mycenae, although he would be locked in a lifelong conflict with Atreus.

Troezen – Troezen would become king of Hyperea at the same time Pittheus became king of Anthea, when Troezen died, the two cities were joined together as Troezen.

Chrysippus – Chrysippus was the only named child not born to Hippodaemia, but this son of Pelops was considered the favourite child.

Chrysippus the son of Pelops

Despite being "illegitimate", Chrysippus was considered to be the favourite son of Pelops, and Hippodameia was said to fear the possibility that her own sons would be overlooked when it came to inheriting from their father.

At one time Chrysippus was abducted by Laius, the father of Oedipus, who had fallen in love with the son of Pelops, but Chrysippus was rescued and returned to his father’s palace, although the favoured son of the king would find no safety there.

Various stories tell of how Chrysippus came to die, although in all probability he was killed by either Atreus or Hippodameia. Pelops though suspected all of his sons for taking a role in the murder of Chrysippus and they were sent away to different points of the Peloponnesus, and many actually flourished.

Hippodameia also feared the wrath of Pelops, and fled to Midea.

The murder of Chrysippus was said to have further perpetuated the curse on the family line.

After Death

There is no mention in ancient texts about the death of Pelops, but it was though that when he did die his bones were laid to rest near Pisa, for his sarcophagus was to be found near the temple of Artemis. The bones of Pelops would continue to be important in Greek mythology, and the divinely made shoulder bone of Pelops would be find further mention.

Firstly, one of the conditions to allow the victory of the Achaeans at Troy was said to be that the bone of Pelops be present amongst the Greeks. Thus, Agamemnon dispatched a ship to bring it from Pisa; unfortunately, the ship and its precious cargo were subsequently lost during a storm off the coast of Eretria.

Then, years later, the ivory bone of Pelops was dredged up form the depths by the net of a fisherman called Demarmenus. Demarmenus took the bone to Delphi in order that he should find out what he to do with it; coincidentally a committee from Elis was also present at Delphi as they sought guidance about a plague ravaging their state.

The two parties were brought together by the Pythia, and so the bone of Pelops returned to Pelop’s homeland. Demarnenus was given the honoured position as guardian of the bone, and the plague rampaging through Elis abated.

The name Pelops in Greek Mythology and History

In Greek mythology, Pelops (Ancient Greek: Πέλοψ , meaning: "dark eyes" or "dark face", derived from pelios 'dark' and ops 'face, eye') may refer to the following three figures:

Pelops, king of Pisa and son of Tantalus

Pelops, son of Agamemnon

Pelops, an Egyptian prince and one of the sons of Aegyptus. He married the Danaid Danais and was killed by her during their wedding night.

Pelops was King of Sparta of the Eurypontid dynasty. He was son of Lykourgos. He was born sometime around 210 BC, but his father soon died that year. Since he was an infant, a regent reigned, first Machanidas and then Nabis. In 199 BC however, Pelops was assassinated by Nabis, who assumed the throne. He was the last of the Eurypontid Dynasty.

Sources

Ovid, Metamorphoses VI, 403-11

Bibliotheca, Epitome II, 3-9; V, 10

Pindar, Olympian Ode I

Sophocles, Electra 504 and Oinomaos Fr. 433

Euripides, Orestes 1024-1062

Diodorus Siculus, Histories 4.73

Hyginus, Fables: 84 - Oenomaus

Pausanias, Description of Greece 5.1.3-7, 5.13.1, 6.21.9, 8.14.10-11

Philostratus the Elder, Imagines 1.30 - Pelops

Philostratus the Younger, Imagines 9 - Pelops

Hyginus, Fabulae, 82 & 83

Tzetzes on Lycophron, 52

Scholia on Euripides, Orestes, 11

Robert Graves. The Greek Myths, section 108 s.v. Tantalus

Scholia on Euripides, Orestes, 4; on Pindar, Olympian Ode, 1. 144

Pseudo-Plutarch, Greek and Roman Parallel Stories, 33

Robert Graves. The Greek Myths, section 110 s.v. The Children of Pelops

Pausanias, Description of Greece, 6. 21. 9–11, with a reference to Megalai Ehoiai fr. 259(a).

Pindar, First Olympian Ode. 71.

Cicero, Tusculanae Disputationes 2.27.67 (noted in Kerenyi 1959:64).

Gordon S. Shrimpton (1991). Theopompus the Historian. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-0837-8.

Burkert, Homo Necans 1983, p 95f.

G. Devereux, "The abduction of Hippodameia as 'aiton' of a Greek animal husbandry rite" ''SMSR 36 (1965), pp 3-25. Burkert, in following Devereux's thesis, attests Herodotus iv.30, Plutarch's Greek Questions 303b and Pausanias 5.5.2.

Diodorus Siculus, 4.74.

Pelops at theoi.com

Pelops at theoi.com

The Geography of Strabo, Vol 4 uchicago.edu

Pindar, First Olympian Ode.

Pausanias, 5.13.1-3.

Adrienne Mayor, The First Fossil Hunters: Paleontology in Greek and Roman Times (Princeton University Press, 2000) discusses the uses made of giant fossil bones in Greek cult and myth.

Pausanias 5.13.4.

"Wikipedia"

"Greek Legends and Myths"