Capaneus

In Greek mythology, Capaneus (Ancient Greek: Καπανεύς) was a son of Hipponous and either Astynome (daughter of Talaus) or Laodice (daughter of Iphis), and husband of Evadne, with whom he fathered Sthenelus. Some call his wife Ianeira.

At the time of Capaneus, Argos was divided into three kingdoms, a division that had occurred during the time of Melampus. Capaneus' link to one of the royal lines of Argos was important though.

As stated above, further links to the royal families of Argos were strengthened when Capaneus married Evadne, a daughter of Iphis. Capaneus then became a father, for Evadne gave birth to a son, Sthenelus.

THE SEVEN AGAINST THEBES

At this time, trouble was occurring in Thebes, for though the sons of Oedipus, Eteocles and Polynices, had agreed to share the throne of Thebes, potentially ruling in alternate years. It was said though that Eteocles, refused to relinquish the throne when it was time for Polynices to rule, and instead Polynices was exiled from Thebes.

Polynices found refuge in Argos, and one of the kings of Argos, Adrastus, then taking note of a prophecy, and married Polynices to his daughter, Argea. Adrastus also promised to raise an army to reclaim the throne of Thebes for Polynices.

This army would be led by seven commanders, the Seven Against Thebes, and although the names of the seven do vary between the surviving sources, Capaneus is always named as one of the Seven.

THE ATTACK ON THEBES

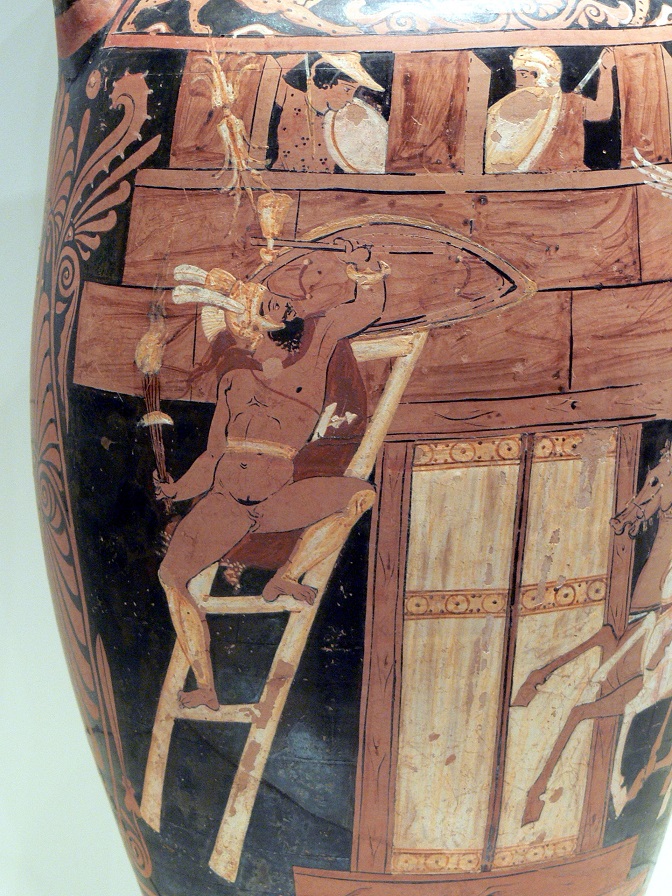

When the Argive army arrived at Thebes, each commander was said to have been given the task of taking one of the seven gates of Thebes, with Capaneus either assailing the Electrian or Ogygian Gate, where he faced either Dryas or Polyphontes as the named defender.

Capaneus was regarded as a great warrior, with immense strength and skill. Capaneus though also had a serious flaw, for he was arrogant in the extreme.

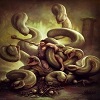

Capaneus would proclaim that even the thunderbolts and lightning of Zeus could not prevent him from taking Thebes.

Such hubris was unlikely to go unnoticed by any god, and of course Zeus took note of the boast. Thus, it was, that as Capaneus scaled a ladder, positioned against the walls of Thebes, so Zeus struck him dead with a bolt of lightning.

Afterwards, as Capaneus’ funeral pyre was being lit, so his wife, Evadne leapt upon the pyre, killing herself. Occasionally, it was said that Capaneus was brought back from the dead by Asclepius’ healing prowess, something which would lead to Asclepius’ own downfall.

Capaneus' story was told by Aeschylus in his play Seven against Thebes, by Euripides in his plays The Suppliants and The Phoenician Women, and by the Roman poet Statius.

HIS DESCENDANT

The attack on Thebes did not go well for the Seven, and it was said that all the attackers, bar Adrastus died in the attempt to take the city; with the sons of Oedipus, Polynices and Eteocles killing each other when they fought.

The defeat of the Seven, gave rise to the tale of the Epigoni, when the sons of the Seven, Sthenelus included, sought to avenge their fathers.

Capaneus himself was never a king of Argos, but his son, Sthenelus succeeded Capaneus’ father-in-law, Iphis, as king. Capaneus’ son would establish himself as hero of note, for he was one of the Epigoni, the sons who avenged their fathers at Thebes, as well as being one of the Achaean leaders at Troy.

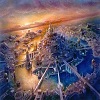

It would then be Capaneus’ grandson, Cylarabes, who would reunite the three kingdoms of Argos into one.

IN DANTE'S DIVINE COMEDY

In the Divine Comedy, Dante sees Capaneus in the seventh circle of Hell. Along with the other blasphemers, or those "violent against God", Capaneus is condemned to lie supine on a plain of burning sand while fire rains down on him. He continues to curse the deity (whom, being a pagan, he addresses as "Giove" i.e. Jupiter) despite the ever harsher pains he thus inflicts upon himself, so that God "thereby should not have glad vengeance."

Virgil strongly condemns Capaneus, but many readers of the Comedy have perceived heroism in his defiance of God's whims even under torture.

The specific section of Dante's Divine Comedy goes as follows:

Capaneus: Circle 7, Inferno 14

A huge and powerful warrior-king who virtually embodies defiance against his highest god, Capaneus is an exemplary blasphemer--with blasphemy understood as direct violence against God. Still, it is striking that Dante selects a pagan character to represent one of the few specifically religious sins punished in hell.

Dante's portrayal of Capaneus in Inferno 14.43-72--his large size and scornful account of Jove striking him down with thunderbolts--is based on the Thebaid, a late Roman epic (by Statius) treating a war waged by seven Greek heroes against the city of Thebes. Capaneus' arrogant defiance of the gods is a running theme in the Thebaid, though Statius' description of the warrior's courage in the scenes leading up to his death reveals elements of Capaneus' nobility as well as his contempt for the gods.

For instance, Capaneus refuses to follow his comrades in a deceitful military operation against the Theban forces under the cover of darkness, insisting instead on fighting fair and square out in the open. Nevertheless, Capaneus' boundless contempt ultimately leads to his demise when he climbs atop the walls protecting the city and directly challenges the gods: "come now, Jupiter, and strive with all your flames against me! Or are you braver at frightening timid maidens with your thunder, and razing the towers of your father-in-law Cadmus?" (Thebaid 10.904-6).

Recalling the similar arrogance displayed by the Giants at Phlegra (and their subsequent defeat), the deity gathers his terrifying weapons and strikes Capaneus with a thunderbolt. His hair and helmet aflame, Capaneus feels the fatal fire burning within and falls from the walls to the ground below. He finally lies outstretched, his lifeless body as vast as a giant's. This is the image inspiring Dante's depiction of Capaneus as a large figure appearing in the defeated pose of the blasphemers, flat on their backs (Inf. 14.22).

Capaneus' continued defiance of Jove in hell draws a harsh response from Virgil, who explains to Dante that this unabated rage only adds to the blasphemer's punishment (Inf. 14.61-72). What do you think? Could Virgil be wrong and Capaneus actually gain a measure of satisfaction from his contempt in the afterlife? Or does the logic of hell require only punishment and suffering?

Sources

Hyginus, Fabulae, 70

Scholia on Euripides, Phoenician Women, 189; on Pindar, Nemean Ode 9. 30

Bibliotheca 3. 10. 8

Scholia on Pindar, Olympian Ode 6. 46

Vegetius. De re militari. 4.21.

Sophocles, Antigone, 133

Bibliotheca 3. 6. 6. – 3. 7. 1

Euripides, Suppliants, 983 ff

Hyginus, Fabulae, 243

Ovid, Metamorphoses, 9. 404; Ars Amatoria, 3. 21

Philostratus the Elder, Images, 2. 31

Aeschylus, Seven Against Thebes, 423 ff

Euripides, Phoenician Women, 1172 ff

Statius, Thebaid, 10. 927