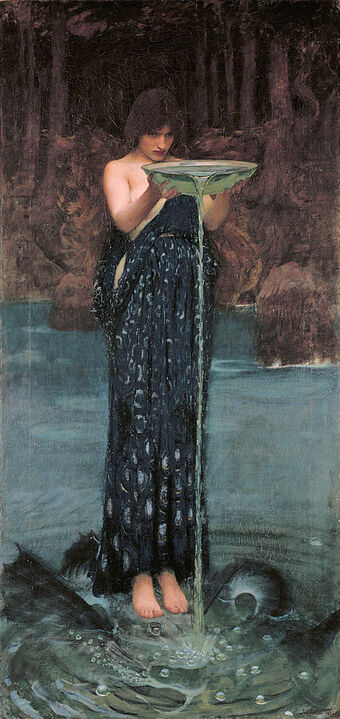

Circe (Kirke)

Circe was one of the most powerful enchantresses of Greek mythology, who some call a witch and some a goddess. Today, Circe is famous as a host of Odysseus and his crew as they sought to return home to Ithaca after the Trojan War.

Circe was a daughter of the Greek sun god Helios, and his wife, the Oceanid Perseis (some sources also mention that Circe's mother was the goddess Hecate). This parentage made Circe sister to another powerful sorceress, Pasiphae, wife of Midas, as well as Perses and Aeetes, famous kings of Greek mythology. Whilst, Perses and Aeetes were not known for their magical abilities, a niece of Circe, Medea certainly was.

To summarize her family tree: By most accounts, she was the daughter of Helios, the Titan sun god, and Perse, one of the three thousand Oceanid nymphs. Her brothers were Aeëtes, keeper of the Golden Fleece, and Perses. Her sister was Pasiphaë, the wife of King Minos and mother of the Minotaur. Other accounts make her the daughter of Hecate, the goddess of witchcraft. She was often confused with Calypso, due to her shifts in behavior and personality, and the association that both of them had with Odysseus.

Comparison of Witch Powers

Of the three female sorceresses, Circe, Pasiphae and Medea, Circe was regarded as the most powerful of the three, and able to concoct powerful potions, but Circe was also said to have power to hide the sun and moon as she willed.

Circe was also known to call upon the assistance of “dark” deities, in the form of Chaos, Nyx and Hecate.

Circe's Island

The home of Circe was said to have been upon the island of Aeaea, for Circe had been brought to the island by her father, Helios, upon the god’s golden chariot.

Aeaea though does not appear on any modern map, and in antiquity there was great debate about where Aeaea was to be found. Locations were given for the island of Aeaea to be found both east and west of Italy, and Apollonius of Rhodes tells of it being south of Elba, but within sight of the Tyrrhenian coastline.

Circe remained an important mythological figure through until the Roman period, where writers told of Aeaea actually being the island of Ponza, or else Mount Circeo (Mount Circaeum), the latter being a mountain surrounded by marshland and sea, rather than being a true island.

Circe's Mansion

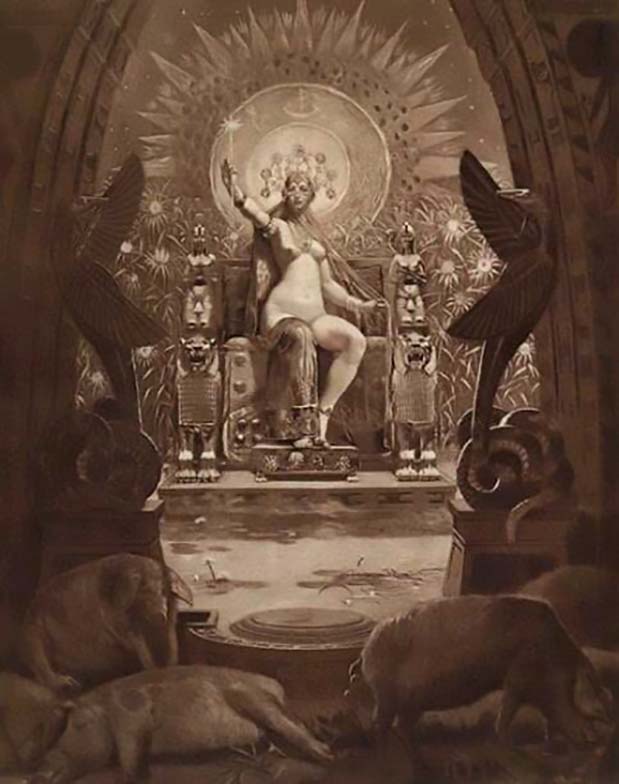

Circe would live within a stone mansion upon Aeaea, a mansion located in a forest clearing. Circe would have her own throne, and was attended to by various nymphs, who also gave flowers and herbs used in Circe’s potions.

Circe also had her own menagerie of animals, lions, bears and wolves, who though wild beast behaved as if they were domesticated animals. Some tell of these animals having been tamed by Circe, but others tell of them being men who had been transformed into animals by the sorceress.

Circe and Glaucus

The theme of transformation was one which appeared in most surviving tales of Circe.

It was said that Circe was in love with Glaucus, a minor sea deity, but Glaucus knew not of this love, for he only had eyes for Scylla, a beautiful maiden. Some tell of Circe poisoning the water in which Scylla bathed, and some tell of Circe giving Glaucus a love potion, which the sea god believed would ensure Scylla fell in love with; in either case, Circe’s potion transformed Scylla into a hideous monster who later became famous for wrecking ships in conjunction with Charybdis.

Circe and Picus

A similar tale of love scorned would be told by Roman writers, when Circe fell in love with Picus, a son of Cronus (Saturn). Circe would seek to seduce Picus, but she was scorned once again, for Picus was in love with Caenns, a daughter of the Roman god Janus.

Picus rejected the advances of Circe, and in retribution recited a spell which transformed in Picus into a woodpecker.

When friends of Picus came to Circe to seek news of their friend, they being unaware of his transformation, Circe then transformed them into other animals, giving rise to much of the fauna found upon Mount Circaeum.

Circe and Odysseus

Circe is most famous for her encounter with Odysseus, as told by Homer and other writers. Odysseus and his men landed upon Aeaea, not knowing where they were, but hoping that this would be a safe refuge after their troubles with Polyphemus and the Laestrygonians.

Quickly though, Odysseus realised that he and his men were in as much trouble as they had previously, for one group of men, who were searching the island, came across Circe’s mansion, and they, bar Eurylochus, are enticed to enter the mansion by Circe herself.

These unwary men partake of food given to them by Circe, but as they ate, they became transformed into swine.

Circe would have used her magic upon Odysseus as well, but the king of Ithaca was aided by Hermes, with the god giving him advice as well as potion to counteract that of Circe.

Subsequently, Circe and Odysseus would become lovers; Circe would thus transform Odysseus back into their previous forms, and for a year Odysseus and his crew lived in a relative paradise.

Eventually, it was time for Odysseus to leave Circe, and Circe gladly gives her lover help to enable him to return home. Odysseus has to travel to the Underworld to seek out the deceased Tiresias, who would be able to tell Odysseus all that Circe could not. Circe thus tells Odysseus how he can enter the Underworld and afterwards, Circe also tells Odysseus how he can safely traverse between Scylla and Charybdis.

Circe and the Argonauts

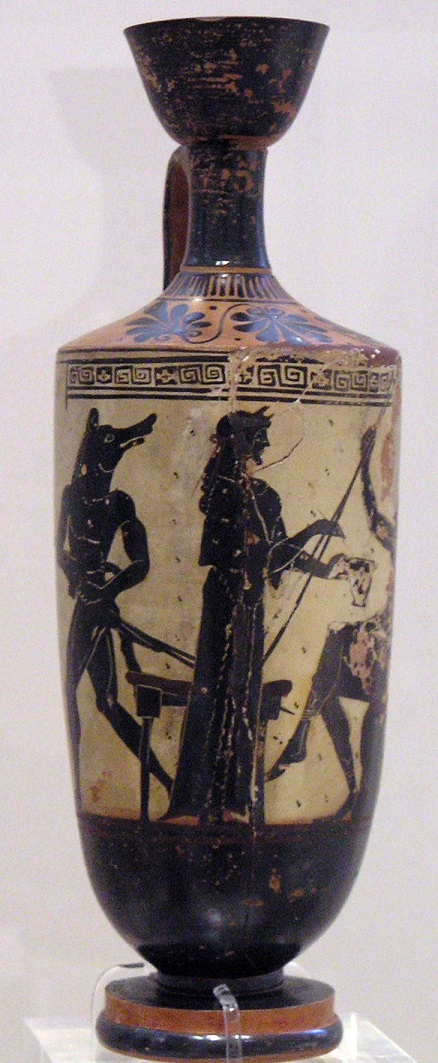

In the generation before Odysseus and his men, Circe had also played host to another band of heroes, for Medea led the Argo to the island of Circe, as Jason and his men fled from Colchis.

To enable the escape of the Argonauts from the Colchian fleet, Medea had killed her own brother, Apsyrtus, and then thrown his dismembered limbs into the sea, delaying her father Aeetes, who sought to retrieve all of the body parts of his son.

For such a crime, Medea and Jason required absolution, and so it was to her aunt hat Medea came, and Circe was thus said to have purified them, allowing them to continue their voyage unmolested.

Circe as Lover, Wife and Mother

As a lover of Odysseus, Circe was said to have become son to three sons by the King of Ithaca; these sons being Agrius, Latinus and Telegonus.

Of these three, Telegonus is the most famous, for as well as being a king of the Etruscans, Telegonus also accidentally killed his father.

For in a tragic final twist, an aged Odysseus was killed by Telegonos, his son by Circe, when he landed on Ithaca and in battle, unknowingly killed his own father.

Subsequently, Telegonus would wed Penelope, and Telemachus, son of Odysseus and Penelope, would wed Circe.

Circe was then said to have made Penelope, Telegonus, and Telemachus immortal through her potions, with all four later said to have resided upon the Islands of the Blest.

---------------------------------

If this stuff is unknown to you, the story is as follows:

In the famous nekyia from Book XI of the Odyssey, the ghost of the blind prophet Teiresias tells Odysseus:

"As for yourself, death shall come to you from the sea, and your life shall ebb away very gently when you are full of years and peace of mind, and your people shall bless you. All that I have said will come true."

This is all the Odyssey ever tells us about Odysseus’s death.

Naturally, later writers came up with more elaborate stories. In a fragment from the lost tragedy The Necromancers, written by the Athenian tragic playwright Aischylos (lived c. 525/524 – c. 456/455 BC), Teiresias gives a much more specific—and much more bizarre—prediction of Odysseus's death:

Another, more elaborate account of Odysseus’s death comes from the Telegoneia (Τηλεγόνεια), a lost poem of the Epic Cycle, which is known only through a surviving summary in the Library of Pseudo-Apollodoros, which is believed to have been written in around the second century AD.

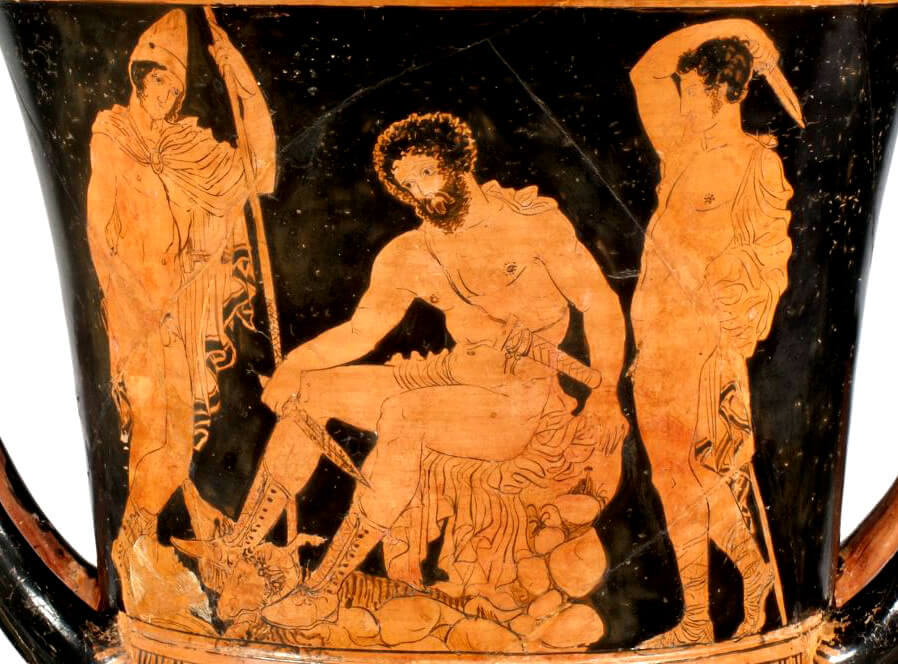

According to the summary of the Telegoneia in the Library, Odysseus had a son with Kirke named Telegonos, who was born after Odysseus left Aiaia. Telegonos was raised by Kirke on Aiaia and, once he was grown, his mother revealed to him who his father was and so he set off to meet his father on Ithaka, armed with a spear fashioned by the god Hephaistos with the deadly stinger of a stingray at the tip.

Telegonos, however, was blown off course by a storm and wound up on a strange island, which, unbeknownst to him, was actually Ithaka. Telegonos pillaged Odysseus’s cattle for food and the now-aged Odysseus came out to defend his property. Neither of them recognized each other, because neither of them had ever seen the other. They fought to the death and Telegonos killed his own father Odysseus with his poisoned spear.

"A heron flying overhead will strike you with dung emptied from its belly. Your aged scalp from which the hair has fallen out will be made to fester by a spine from its food gathered in the sea."

At the last moment, as Odysseus lay dying on the ground, he and Telegonos suddenly recognized each other as father and son, but, by this point, it was already far too late for Telegonos to save his father. Telegonos brought Odysseus’s body to Penelope and to Telemachos, the son of Odysseus and Penelope. Together, they went back to Aeaea where they buried his body; hence, they gave Odysseus a proper burial.

In the end, Kirke showed up and made Telegonos, Telemachos, and Penelope all immortal. Then, Telegonos married Penelope and Telemachos married Kirke.

---------------------------------

Finally, some also call the son of Circe, Latinus, king of Latium, who would welcome Aeneas to his kingdom, though nothing of note is said about Agrius.

Roman writers would also add three further sons of Circe and Odysseus, Romus, Anteias, and Ardeias, named, in some sources, as the founders of the Italian cities of Rome, Antium and Ardea.

Later mythology, particularly in the work of Nonnus, also named Faunus (Phaunos) the rustic god as a son of Circe and Odysseus, but Faunus was more commonly considered to be an equivalent to Pan.

Other texts

Towards the end of Hesiod's Theogony (c. 700 BCE), it is stated that Circe bore Odysseus three sons: Ardeas or Agrius (otherwise unknown); Latinus; and Telegonus, who ruled over the Tyrsenoi, that is the Etruscans. The Telegony, an epic now lost, relates the later history of the last of these. Circe eventually informed him who his absent father was and, when he set out to find Odysseus, gave him a poisoned spear. With this he killed his father unknowingly. Telegonus then brought back his father's corpse to Aeaea, together with Penelope and Odysseus' other son Telemachus. After burying Odysseus, Circe made the others immortal.

In the 5th-century CE epic Dionysiaca, author Nonnus mentions Phaunos, Circe's son by the sea god Poseidon.

According to Lycophron's 3rd-century BCE poem Alexandra, and John Tzetzes' scholia on it, Circe used magical herbs to bring Odysseus back to life after he had been killed by Telegonus. Odysseus then gave Telemachus to Circe's daughter Cassiphone in marriage. Some time later, Telemachus had a quarrel with his mother-in-law and killed her; Cassiphone then killed Telemachus to avenge her mother's death. On hearing of this, Odysseus died of grief.

In his 3rd-century BCE epic, the Argonautica, Apollonius Rhodius relates that Circe purified the Argonauts for the death of Absyrtus, possibly reflecting an early tradition. In this poem, the animals that surround her are not former lovers transformed but primeval 'beasts, not resembling the beasts of the wild, nor yet like men in body, but with a medley of limbs'.

Dionysius of Halicarnassus (1.72.5) cites Xenagoras, the 2nd-century BCE historian, as claiming that Odysseus and Circe had three sons: Rhomus, Anteias, and Ardeias, who respectively founded three cities called by their names: Rome, Antium, and Ardea.

Three ancient plays about Circe have been lost: the work of the tragedian Aeschylus and of the 4th-century BCE comic dramatists Ephippus of Athens and Anaxilas. The first told the story of Odysseus' encounter with Circe. Vase paintings from the period suggest that Odysseus' half-transformed animal-men formed the chorus in place of the usual Satyrs. Fragments of Anaxilas also mention the transformation and one of the characters complains of the impossibility of scratching his face now that he is a pig.

Some say she was exiled to the solitary island of Aeaea by her subjects and her father Helios for killing her husband, the prince of Colchis. Later traditions tell of her leaving or even destroying the island and moving to Italy, where she was identified with Cape Circeo.

The theme of turning men into a variety of animals was elaborated by later writers, especially in Latin. In Virgil's Aeneid, Aeneas skirts the Italian island where Circe now dwells, and hears the cries of her many male victims, who now number more than the pigs of earlier accounts:

"The roars of lions that refuse the chain, / The grunts of bristled boars, and groans of bears, / And herds of howling wolves that stun the sailors' ears."

Ovid's 1st-century Metamorphoses collects more transformation stories in its 14th book. The fourth episode covers Circe's encounter with Ulysses (Roman names of Odysseus). The first episode in that book deals with the story of Glaucus and Scylla, in which the enamoured sea-god seeks a love potion to win Scylla's love, only to have the sorceress fall in love with him. When she is unsuccessful, she takes revenge on her rival by turning Scylla into a monster (lines 1–74). The story of the Latian king Picus is told in the fifth episode (and also alluded to in the Aeneid). Circe fell in love with him too; when he preferred to remain faithful to his wife Canens, she turned him into a woodpecker (lines 308–440).

Plutarch took up the theme in a lively dialogue that was later to have several imitators. Contained in his 1st-century Moralia is the Gryllus episode in which Circe allows Odysseus to interview a fellow Greek turned into a pig. There his interlocutor informs Odysseus that his present existence is preferable to the human. They then engage in a philosophical dialogue in which every human value is questioned and beasts are proved to be of superior wisdom and virtue.

Sources

GREEK

Homer, The Odyssey - Greek Epic C8th B.C.

Homerica, Homer's Epigrams - Greek Epic C8th - 7th B.C.

Hesiod, Theogony - Greek Epic C8th - 7th B.C.

Epic Cycle, The Returns Fragments - Greek Epic C7th - 6th B.C.

Epic Cycle, The Telegony Fragments - Greek Epic C8th - 6th B.C.

Apollodorus, The Library - Greek Mythography C2nd A.D.

Apollonius Rhodius, The Argonautica - Greek Epic C3rd B.C.

Lycophron, Alexandra - Greek Poetry C3rd B.C.

Parthenius, Love Romances - Greek Mythography C1st B.C.

Diodorus Siculus, The Library of History - Greek History C1st B.C.

Strabo, Geography - Greek Geography C1st B.C. - C1st A.D.

Pausanias, Description of Greece - Greek Travelogue C2nd A.D.

Plutarch, Parallel Stories - Greek Historian C1st - 2nd A.D.

Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae - Greek Rhetoric C3rd A.D.

Ptolemy Hephaestion, New History - Greek Mythography C1st - 2nd A.D.

Quintus Smyrnaeus, Fall of Troy - Greek Epic C4th A.D.

Greek Papyri III Anonymous, Odyssey Fragments - Greek Poetry C3rd - 4th A.D.

Nonnus, Dionysiaca - Greek Epic C5th A.D.

ROMAN

Hyginus, Fabulae - Latin Mythography C2nd A.D.

Ovid, Metamorphoses - Latin Epic C1st B.C. - C1st A.D.

Ovid, Fasti - Latin Poetry C1st B.C. - C1st A.D.

Virgil, Aeneid - Latin Epic C1st B.C.

Propertius, Elegies - Latin Elegy C1st B.C.

Cicero, De Natura Deorum - Latin Rhetoric C1st B.C.

Valerius Flaccus, The Argonautica - Latin Epic C1st A.D.

Statius, Thebaid - Latin Epic C1st A.D.

OTHER

Grimal, Pierre, The Dictionary of Classical Mythology, Wiley-Blackwell, 1996.

Milton, John, A Masque Presented at Ludlow Castle [Comus] line 153 "mother Circe".

Smith, William; Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, London (1873). "Circe".

Miller, Madeline; Circe, Little Brown and Company (2018).

"Theoi"

"Greek Legends and Myths"

"Wikipedia"