Trojan War

The Trojan War is probably one of the most important events that have been narrated in Greek mythology. It was a war that broke out between the Achaeans (the Greeks) and the city of Troy. The best known narration of this event is the epic poem Iliad, written by Homer.

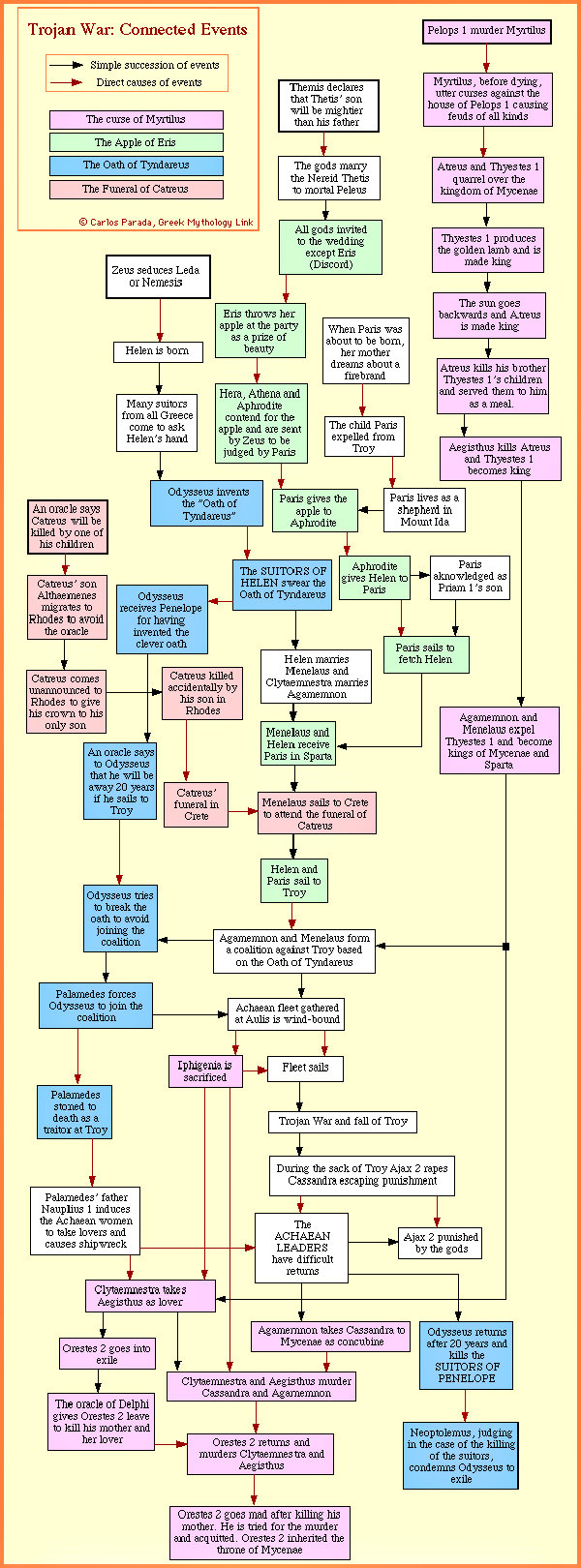

Zeus believed that the number of humans populating the Earth was too high and decided it was time to decrease it. Moreover, as he had various affairs with mortal women and fathered demigod children, he thought it would be good to get rid of them. He formed a plan after he learned of two prophecies; one of them said that he would be dethroned by one of his sons, just like he had done with his own father, Cronus; the other prophecy mentioned that the sea nymph Thetis, for whom Zeus had fallen, would give birth to a son that would surpass his father in glory. So, Zeus decided to marry Thetis to King Peleus.

The god of gods organised a grand feast in celebration of Peleus' and Thetis' marriage, in which all of the gods and important figures were invited, except the goddess of strife, Eris. The goddess was stopped at the door by Hermes, infuriating her. Before she left, she threw her gift amidst the guests; the Apple of Discord, a golden apple on which the words "to the fairest" had been inscribed. Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite started quarreling over who should be the one to take the apple, and demanded that Zeus decide on this matter. Zeus knew that if he made a choice, he would cause the anger of the other two that wouldn't be picked, and decided to abstain; instead, he appointed Paris, the young prince of Troy, as the judge. Paris could not make a decision, even after seeing the three goddesses naked, so they started bribing him; Hera said that he would get political power and be the ruler of the continent of Asia; Athena would give him wisdom and great skills in battle; and Aphrodite offered him the most beautiful woman in the world, Helen of Sparta. Paris gave the apple to Aphrodite, and returned to Troy.

Peleus and Thetis had a son, Achilles, for whom two prophecies had been made; one was that he would either lead an uneventful but long life, or a glorious one but he would die young at a battlefield; the other prophecy was that without his help, the city of Troy would never fall. Afraid for her son's life, Thetis decided to grant immortality to him. When he was still an infant, she took him to the River Styx, one of the rivers that ran through the Underworld, and dipped him in the waters, thus making him invulnerable. However, Thetis did not realise that the heel of the boy, from which she was holding him, did not touch the waters and remained mortal; this would later be the doom of Achilles, and is the origin of the modern day phrase "Achilles' heel", signifying a vulnerable point. After the ritual, she dressed him as a girl and hid him at the court of King Lycomedes of Skyros.

Meanwhile, the most beautiful woman in the world, Helen, was the daughter of King Tyndareus of Sparta, and many noble suitors had arrived to claim her hand in marriage. Tyndareus did not want to make a choice for fear of causing political tensions, and stalled the decision. One of the suitors, Odysseus, offered to help solve the situation, asking in return for the hand of Penelope; Tyndareus agreed, and Odysseus asked that all suitors swear an oath that they would protect the couple no matter who the groom would be. After the oath was taken, Tyndareus picked Menelaus as his daughter's husband, effectively making him the successor of the Spartan throne through Helen. However, Menelaus caused Aphrodite's wrath, after failing to sacrifice one hundred oxen for her as he had promised; this is why Aphrodite decided to help Paris win Helen's heart.

The goddess made a plan and disguised Paris as a diplomatic emissary. He then went to Sparta, where Helen welcomed him, while her husband was away in Crete to bury his uncle. At that point, the god of love, Eros, shot an arrow to her, thus causing her to fall in love with the Trojan prince. The two lovers eloped and left for Troy.

Menelaus returned home and realised what had happened. Along with Odysseus, they went to Troy to get Helen back, but all diplomatic attempts failed. So, Menelaus invoked the Oath of Tyndareus, and, helped by his brother Agamemnon, called all Achaean leaders who had previously been the suitors of Helen to fulfill their oath. They also needed the help of Achilles, as they knew of the prophecy that Troy would only fall with his help. Odysseus, Telamonian Ajax and Phoenix went to Skyros where they knew Achilles was hidden disguised as a woman. There, they either blew a warhorn, on the sound of which Achilles was the only woman that took a spear in hand; or they appeared as merchants selling jewels and weapons, and Achilles was the only woman interested in the latter.

Having Achilles with them, all leaders gathered at the port of Aulis. A sacrifice was made to Apollo, and the god sent an omen; the Achaeans saw a snake appear from the altar that slithered to a bird's nest, where it ate the mother and her nine babies before it was turned to stone. The seer Calchas said that this meant Troy would fall in the tenth year of the war. The Achaeans set sail for Troy, although no one knew the way. By mistake, they arrived in Mysia, ruled by King Telephus; after a battle, during which Achilles wounded the king, the Achaean ships sailed but a storm scattered them. Telephus' wound would not heal, and an oracle told him it would be healed by the person who inflicted it. When Telephus confronted Achilles, he said he did not have any medical knowledge; Odysseus then proposed that the spear that caused the wound might help, so pieces of metal were used and the wound was healed. Telephus then told them how they would reach Troy.

Due to the storm that scattered the fleet, the Achaean leaders eventually gathered in Aulis again eight years later. However, they were unable to set sail because there was no wind. Calchas realised that this was a punishment from the goddess Artemis, who was furious at Agamemnon for killing a sacred deer. Artemis demanded that Agamemnon's daughter Iphigenia be sacrificed. Although Agamemnon initially refused, he reluctantly agreed in the end, and tricked his wife Clytemnestra and Iphigenia to go to Aulis, saying that Iphigenia was to marry Achilles. When they arrived to Aulis and understood what was going on, Clytemnestra cursed Agamemnon and was the reason she murdered him after the war was over. Iphigenia gracefully accepted her fate and placed herself on the altar; however, just as Calchas was about to sacrifice her, Artemis substituted the woman for a deer and took her to Tauris where she became the goddess' high priestess. Nevertheless, no one saw what happened on the altar except Calchas, who was bound not to say anything.

The winds picked up again after the sacrifice and the Achaean fleet was finally able to set sail. They made a stop at the island of Tenedos, where Achilles killed the king, who was the son of the god Apollo. Thetis had warned her son not to kill the king, lest he be killed by the god himself. This was also a foretelling of the hero's fate. While on the island, the Greeks sent a diplomatic mission to Troy asking for Helen, but it was refused into the city. So the fleet sailed on its final leg of the journey.

When the fleet arrived, they were all reluctant to disembark, as a prophecy said that the first Greek to step on Trojan soil would be the first to die in the war. Finally, Odysseus decided to disembark first; however, he threw his shield on the ground and stepped on it, while Protesilaus who followed him landed on the ground. Thus it was Protesilaus who died first, during a single combat against the Trojan prince Hector.

The siege of Troy lasted nine years, but not being complete, Troy was still able to maintain trade links with other Asian cities, as well as get reinforcements. At the end of the ninth year, the Achaean army mutinied and demanded that they return home, but Achilles eventually convinced them to stay longer.

On the tenth year, the priest of Apollo, Chryses, went to Agamemnon and asked for his daughter Chryseis' return, who had been taken as a concubine. Agamemnon refused, and Chryses prayed to Apollo, who inflicted the Greek army with plague. Agamemnon returned Chryseis to her father, but instead took Achilles' concubine for his own. Achilles, infuriated, said he would no longer fight and stayed in his tent. Although the Achaeans initially won a few battles, Achilles' refusal to fight led to a series of defeats, to the point that the Trojans almost set fire to the Greek ships. Then, Patroclus, a close friend of Achilles, took command of the Myrmidon army, but was slain in battle by Hector. Achilles, maddened with grief, swore vengeance; Agamemnon returned the concubine back to him and the two leaders reconciled.

The Greek army was again victorious, and Achilles eventually managed to kill Hector; he refused to give Hector's body to the Trojans for burial, and instead, he desecrated it by dragging it with his chariot in front of the city walls. He eventually agreed to return it, after King Priam of Troy pleaded for his son's proper burial.

Achilles later died by a poisonous arrow that Paris shot against him. The arrow was guided by the god Apollo and hit Achilles on his heel, which was the only vulnerable spot of the hero's body. Achilles was burned on a funeral pyre and his bones were mixed with those of his close friend Patroclus. Paris was killed later by Philoctetes, using Heracles' bow.

Odysseus devised a plan to end the war for good. He asked that a wooden horse be built that was hollow inside. Soldiers hid in the interior of the horse, which was brought in front of the city gates, saying that it was a gift from the Greeks, showing the withdrawal of the Greek army and the end of the war. The Trojans happily accepted and brought the horse inside the city. They then started feasting and celebrating the victory. During the night, the Greek soldiers went out of the horse and started slaying the drunk Trojans. In the battle that followed, a huge number of soldiers died but eventually, Troy fell. The Greeks burned it and raided it, at the same time committing offences against many gods, by destroying temples and sacred grounds. Although victorious, most heroes and Greek soldiers either never returned home or returned after many adventures, as the gods were infuriated.

The Trojan War marked the end of the Heroic Age of Man, according to Hesiodus, and the transition of the world to the Iron Age. Zeus' attempt to depopulate the earth and kill a number of demigods and heroes proved successful.

THE TROJAN HORSE

The Trojan Horse is a story from the Trojan War about the subterfuge that the Greeks used to enter the independent city of Troy and win the war. In the canonical version, after a fruitless 10-year siege, the Greeks constructed a huge wooden horse and hid a select force of men inside, including Odysseus.

The Greeks pretended to sail away, and the Trojans pulled the horse into their city as a victory trophy. That night the Greek force crept out of the horse and opened the gates for the rest of the Greek army, which had sailed back under cover of night. The Greeks entered and destroyed the city of Troy, ending the war.

Metaphorically, a "Trojan horse" has come to mean any trick or stratagem that causes a target to invite a foe into a securely protected bastion or place. A malicious computer program that tricks users into willingly running it is also called a "Trojan horse" or simply a "Trojan".

The main ancient source for the story is the Aeneid of Virgil, a Latin epic poem from the time of Augustus. The event is also referred to in Homer's Odyssey. In the Greek tradition, the horse is called the "wooden horse" (Ancient Greek: δούρειος ἵππος).

In more detail...

Today, the main source for the Trojan War is the Iliad by the Greek poet Homer, but this epic poem ends prior to the events linked with the Trojan Horse, although Homer does make mention of the Wooden Horse in the Odyssey.

The Iliad and the Odyssey are the only two surviving complete works from the “Epic Cycle”, and the lost works Little Iliad (attributed to Lesches) and Iliou Persis (Arctinus) are more likely to have dealt with the Trojan Horse. Despite this details of the Wooden Horse can be garnered from other ancient sources, including Virgil’s Aeneid.

Before the Trojan Horse, war had dragged on between the Achaean forces of Agamemnon and the defenders of Troy for ten years, and whilst cities allied to Troy had fallen to the Achaeans, the walls of Troy still held firm.

Despite both sides losing their greatest warriors, Achilles on the Greek side, and Hector, on the Trojan, neither side could gain a decisive advantage.

Prophecies were made, by Calchas and later Helenus, about how Troy could fall, but even with the bow and arrows of Heracles, the son of Achilles, and the stolen Palladium in the Achaean camp, still Troy held firm.

The likes of Neoptolemus and Philoctetes were keen to continue fighting, but both were relatively new to the battlefield, for the other battle weary Achaean heroes, it was decided that now was the time for subterfuge rather than conflict.

Thus the idea of the Wooden Horse was put forward. Surviving sources give credit to either Odysseus, under the guidance of the goddess Athena, or to the seer Helenus, for the concept of the Trojan Horse. The idea being that a large wooden horse would be constructed of sufficient size that a number of heroes could hide inside it, and then some method of enticing the Trojans to take the horse inside Troy must be devised.

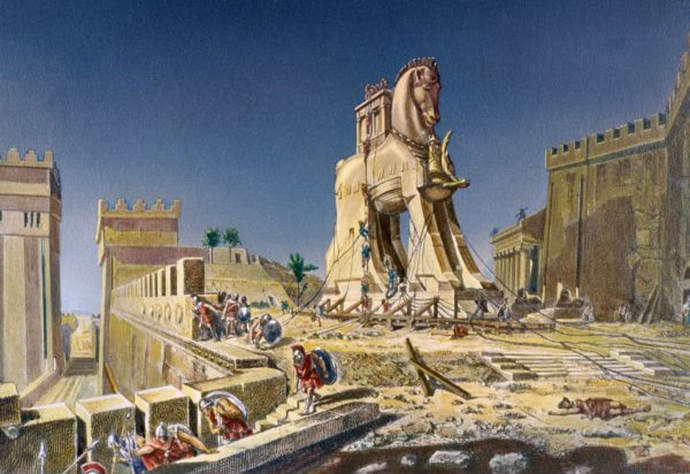

With the idea in place, design and construction was given over to Epeius, son of Panopeus, whilst Ajax the Lesser assisted. Wood was cut from Mount Ida, and for three days the Achaeans toiled to craft a horse like structure upon wheels. Then touches including hooves of bronze and a bridle of ivory and bronze were added to make the Wooden Horse more elegant.

The people of Troy saw the Wooden Horse being built, but they failed to see the hidden compartment inside the horse’s belly, or the ladder inside, or indeed the holes in the horse’s mouth which allowed air into the hidden section.

With the Trojan Horse constructed a number of the Achaean heroes secreted themselves into the hidden compartment.

Ancient sources state that anywhere between 23 and 50 Achaean heroes were to be found in the belly of the Wooden Horse, with the Byzantine poet John Tzetes suggesting 23 heroes, whilst 50 names appear in the Bibliotheca.

Later on it was common to name 40 heroes as being inside the Trojan Horse. The most famous of these heroes were perhaps:

Odysseus – King of Ithaca, inheritor of the armour of Achilles, and the most cunning of all the Achaean heroes.

Ajax the Lesser – King of Locris, and known for his speed of foot, and his skill with the spear.

Calchas – the Achaean seer, whose prophecies and counsel Agamemnon relied heavily upon throughout the war, or at least until the arrival in the Greek camp of Helenus.

Diomedes – King of Argos, named the greatest of the Achaean heroes following the death of Achilles and even went as far as injuring Ares and Aphrodite.

Idomeneus – King of Crete, hero who defended against Hector, and killed 20 Trojan heroes.

Menelaus – King of Sparta, husband of Helen, and brother of Agamemnon.

Neoptolemus – son of Achilles, who according to a prophecy had to fight at Troy in order for the Achaeans to be victorious.

Philoctetes – Son of Poeas, and the owner of Heracles bow and arrows, late comer to the fighting but highly skilled with the bow.

Teucer – Son of Telamon and another noted archer in the Achaean ranks.

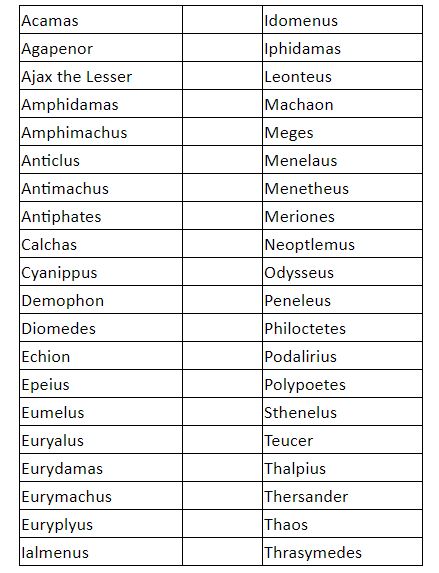

List of Greeks within the Wooden Horse

With heroes hidden inside the Wooden Horse, the rest of the Achaean army now burnt their camp, boarded their ships, and set sail, giving the appearance that they were abandoning the battlefield and war. The Achaean’s of course had not sailed far, perhaps only as far as Tenedos, and were now awaiting the signal to return.

The next morning, the Trojans saw that their enemies were no longer camped outside their city, and all that remained of the Achaean presence was a large Wooden Horse.

All was thus far going as planned for the Achaeans but still they needed the Trojans to take the Wooden Horse inside of Troy to allow a successful conclusion to the plan.

It had thus been decided that a Greek hero must stay behind to try and convince the Trojans to move the Wooden Horse from where it had been built; and this Achaean hero proved to be Sinon, son of Aesimus.

Sinon was of course captured by the Trojans, and now he commenced to tell his “tale”. Sinon would tell his Trojan captors how he had fled the Achaean camp when he had learnt that he was to be sacrificed to allow for fair winds for the Achaean fleet, just as Iphigenia had been ten years before.

This tale gave a plausible reason for Sinon’s presence and thus Sinon continued with his story, telling the Trojans that the Wooden Horse had been built as a monument to the goddess Athena. Sinon also told the Trojans that the Wooden Horse had been built on such a large scale to ensure that it would not fit through the main gate of Troy, thus preventing the Trojans taking the horse, and gaining the blessing of Athena from it. This part of the tale was of course meant to convince the Trojans to move the Wooden Horse.

The majority of the Trojans who listened to the words of Sinon believed them, but there were doubters too.

The first of these doubters was Laocoon, a priest of Apollo within Troy, who Virgil had utter the immortal words “I fear the Greeks, even when bringing gifts”, and the priest even went as far as attempting to hit the flank of the Trojan Horse with his spear. Before Laocoon could cause harm to the plan of the Achaeans, Poseidon who was allied to the Greeks, sent forth sea serpents who strangled Laocoon and his sons.

Cassandra, the seer daughter of King Priam, also warned of the dangers of bringing the Wooden Horse into Troy, but Cassandra was cursed to always prophesise correctly but never to be believed.

Sinon’s were thus believed, and the Achaean was given his freedom by King Priam, and allowed to wander around Troy, whilst the Trojans planned on how to get the Wooden Horse into Troy.

Eventually, the Trojans knocked through part of the wall surrounding the Scaean Gate, but in doing so damaged part of the Tomb of Laomedon, thus nullifying a prophecy that said Troy would never fall if Laomedon’s tomb remained intact.

Once the Trojan Horse was inside Troy, a massive celebration was undertaken by the whole city, and yet the heroes inside the Wooden Horse still had one more danger to overcome. Somehow Helen saw the Wooden Horse for what it was, and walking around it, Helen would imitate the voices of the women married to the Achaean heroes inside. Helen’s purpose in doing so is often debated, but it is generally considered that she was displaying her own cleverness, rather than aiding the Trojans. In any case, despite hearing the voices of their wives, not one of the hidden Achaeans responded to the call.

As night fell, the celebrations in Troy continued, until the majority of the population of Troy were in a drunken stupor. Then, either Sinon from the outside, or Epeius within, unlocked the hatch to the belly of the Trojan Horse, and deployed the ladder; and one-by-one the Achaean heroes within descended Troy.

At the same time, a signal light was lit, either by Sinon or Helen, recalling the Achaean fleet from its anchorage at Tenedos.

Some of the Achaean heroes made their way to the gates of Troy, and silently opened them up, before guarding them to prevent their closure again; and whilst these men awaited the return of the rest of the Achaean army.

Other heroes previously hidden with the Trojan Horse, now started to kill the slumbering Trojan heroes and soldiers. This killing soon turned into a slaughter, and eventually it was said there was but one male survivor of Troy, Aeneas; whilst many of the Trojan Women had become prizes of war.

Thus the Trojan Horse had helped to achieve what ten years of fighting could not, the fall of the mighty city of Troy.

Sources

Apollodorus, Gods & Heroes of the Greeks: The Library of Apollodorus, translated by Michael Simpson, The University of Massachusetts Press, (1976).

Apollodorus, Apollodorus: The Library, translated by Sir James George Frazer, two volumes, Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press and London: William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Volume 1 and Volume 2.

Euripides, Andromache, in Euripides: Children of Heracles, Hippolytus, Andromache, Hecuba, with an English translation by David Kovacs. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. (1996).

Euripides, Helen, in The Complete Greek Drama, edited by Whitney J. Oates and Eugene O'Neill, Jr. in two volumes. 1. Helen, translated by E. P. Coleridge. New York. Random House. 1938.

Euripides, Hecuba, in The Complete Greek Drama, edited by Whitney J. Oates and Eugene O'Neill, Jr. in two volumes. 1. Hecuba, translated by E. P. Coleridge. New York. Random House. 1938.

Herodotus, Histories, A. D. Godley (translator), Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1920.

Pausanias, Description of Greece, (Loeb Classical Library) translated by W. H. S. Jones; Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. (1918). Vol 1, Books I–II, ISBN 0-674-99104-4; Vol 2, Books III–V, ISBN 0-674-99207-5; Vol 3, Books VI–VIII.21; Vol 4, Books VIII.22–X.

Proclus, Chrestomathy, in Fragments of the Kypria translated by H.G. Evelyn-White, 1914 (public domain).

Proclus, Proclus' Summary of the Epic Cycle, trans. Gregory Nagy.

Quintus Smyrnaeus, Posthomerica, in Quintus Smyrnaeus: The Fall of Troy, Arthur Sanders Way (Ed. & Trans.), Loeb Classics #19; Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA. (1913).

Strabo, Geography,

Greek Legends and Myths

[1] "Greek Mythology"